Stage and Screen, 1936. Starring Rex Lease, Nancy Caswell, Reed Howes, Chief Thundercloud, Dorothy Gulliver, George Chesebro, Lona Andre, Milburn Morante, Josef Swickard, Bobby Nelson, William Farnum, Marty Joyce, Robert Walker, Frank McGlynn Jr., Jack Mulhall, Ruth Mix.

Moved by a premonition of his coming death, revered Sioux medicine man True Eagle announces that his ceremonial arrow–which is carved with signs that give the location of a secret and sacred “medicine cave” somewhere in the Black Hills–will be jointly held after his passing by his niece and nephew, cousins Red Fawn (Dorothy Gulliver) and Young Wolf (Chief Thundercloud). The surly Young Wolf is disgusted at the idea of having to share his power with a squaw–and is even more annoyed when the arrow vanishes, after True Eagle is killed in an attack on a wagon train. Knowing that one of the settlers who survived the attack must have taken the arrow, Young Wolf strikes a bargain with Tom Blade (Reed Howes), a shady saloon proprietor who sells whisky to the Indians and engages in other acts of frontier criminality. Blade and his men are to track down the surviving settlers listed in the wagon train’s log book, and thus help Young Wolf recover the arrow; Blade happily acquiesces in this scheme when he learns that the medicine cave is rich in gold. Blade and his gang quickly locate (and kill) the men named in the log, until only Major Trent (Josef Swickard), an ex-Confederate medical officer, remains. Trent, of course, is the actual possessor of the coveted arrow, and soon finds himself, his daughter Barbara (Nancy Caswell), and his grandson Bobby (Bobby Nelson) menaced by Blade, Young Wolf, and their respective followers. However, Army scout Kit Cardigan (Rex Lease), the son of one of the pioneers murdered by Blade, soon gets on the trail of Blade’s gang and becomes the Trent family’s protector; the kindly Red Fawn also does her best to shield the Trents and Kit from her cousin Young Wolf’s wrath, while attempting to recover the arrow herself. To complicate matters further, the embittered Lieutenant Roberts (George Chesebro), a dishonorably discharged cavalry officer, discovers the value of the arrow and sets out to steal it–to the dismay of Blade’s tough but honest saloon-keeping partner Belle Meade (Lona Andre), who loves Roberts and believes he can still turn his life around. As the ensuing battle for the arrow plays out, another conflict is brewing in the Black Hills region; Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse are laying plans for war with Colonel Custer’s (Frank McGlynn Jr.) 7th Cavalry at the Little Big Horn, where the two forces will eventually meet in a battle that will become famous as Custer’s Last Stand.

Above: True Eagle (Carl Mathews) holds the mystic medicine arrow high.

One has to admire Louis and Adrian Weiss–the father and son who bossed the short-lived “Stage and Screen Productions”–for conceiving as ambitious a serial as Custer’s Last Stand; its huge cast of characters, its multiple subplots, and its combination of fiction with history is more reminiscent of the novels of Walter Scott or James Fenimore Cooper than of other movie serials. Unfortunately, the Weiss outfit simply lacked the budget to make their historical epic a success; the serial is such a shoddily-produced affair that it must be ranked as a failure, albeit a unique and fascinating one.

The historical material in Custer is, surprisingly, rather more accurate than in many bigger-budgeted features. Custer is correctly designated as a colonel, not a general; the Last Stand is presented complete with details like the empty Indian village, Custer’s division of his forces, the escape of the Indian scout Curley in a blanket, and Major Reno’s refusal to advance after encountering opposition; Custer’s wartime service at Gettysburg with the Michigan Cavalry and his campaign against the Cheyenne chief Black Kettle are specifically referred to; Nelson A. Miles and George Crook, other notable officers in the Midwestern Indian wars, are mentioned by name; Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane make extended cameos, not only looking very like their real-life counterparts but also exhibiting some of said counterparts’ quirks (the screen Hickok, like the real one, makes a point of sitting with his back to the wall when he enters the saloon). This attention to historical detail can almost certainly be attributed to the presence of George Arthur Durlam on the serial’s screenwriting team–seeing as he later wrote, produced, and directed a series of American-history shorts for an outfit called “Academic Film Company.”

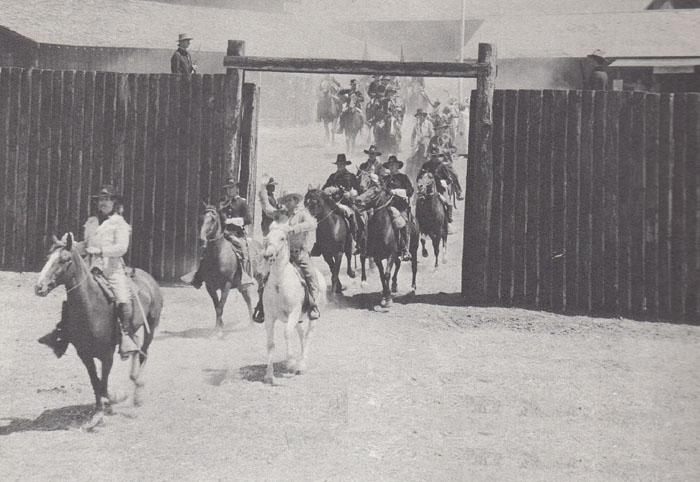

Above: Shots from the serial’s Little Big Horn sequence.

Durlam’s historical material, however, isn’t meshed very effectively with Custer’s fictional elements (which were probably provided largely by the serial’s other two writers, Eddie Granneman and William Lively). The medicine-arrow plot and the Custer-versus-the-Sioux plot are never satisfactorily linked together; Custer, Sitting Bull, and Crazy Horse remain in the background most of the time, and the battle of the Little Big Horn only really impacts two of the serial’s major characters (Roberts and Belle Meade)–unlike the real-life Fort William Henry massacre in Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans and the serial version of the same, which directly affected all of the prominent players in the story. A better-structured piece of historical fiction would have let the arrow and the characters pursuing it play a pivotal part in the buildup to Little Big Horn or in the fight itself; as it is, the legendary battle remains so disconnected from the main storyline that it feels more like an addendum than a dramatic climax.

The main storyline itself quickly grows a bit tiresome, devolving at it does into a repetitive tug-of-war over the medicine arrow; this struggle is temporarily sidelined later in the serial by the villains’ sudden decision to steal an Army payroll–which makes the serial’s plotting seem even more lopsided, but does provide some welcome narrative variety. Further breaks from the arrow hunt are provided by multiple character-driven subplots, although these subsidiary storylines–and the characters involved–vary greatly in complexity. The romance between Kit and Barbara is severely underdeveloped (especially when compared to similar romances in Universal’s Western serials), while Major Trent’s ferocious hatred of “Yankees”–which one expects to complicate his daughter Barbara’s relationship with Army man Kit–is completely forgotten after being strongly emphasized in the early chapters. Red Fawn’s affectionate interest in Kit is also given short shrift, although it does lead to a farewell scene that was obviously intended to be touching (but is so clumsily-written that it falls flat).

Above: Rex Lease hands over the arrow to Dorothy Gulliver (along with some very awkwardly-phrased parting remarks).

The power struggle between the patient Red Fawn and the resentful Young Wolf is given more attention than the serial’s romantic entanglements; it’s offbeat and fairly interesting, and culminates in memorably ironic fashion. The best of the serial’s subplots, however, is the one centering around the disgraced Lieutenant Roberts; his interactions with his former friend Lieutenant Cook and with Belle Meade could have been better-written, but are still compelling and often genuinely moving; the conclusion to his character arc is one of the serial’s dramatic highlights. The campaign of Indian Agent Fitzpatrick and Wild Bill Hickok to clean up the outlaw-ridden town of Blackpool at first promises plenty of excitement, but this plot thread is disappointingly abandoned not long after Hickok makes his first entrance; far more footage is (irritatingly) devoted to young Bobby Trent’s attempts to teach his dull-witted friend Buzz how to scout and blow a bugle.

The writers’ efforts to keep each of these subplot fresh in the viewers’ mind, their painstaking attempts to give each member of the huge cast of characters enough screen time, and the sheer necessity of filling out fifteen lengthy chapters on a low budget all combine to make Custer a decidedly slow-paced serial; dialogue scenes are numerous, and are often dragged out to ridiculous lengths (like the Chapter Seven sequence that has Kit laboriously assembling an Indian disguise that’s penetrated by the villains almost immediately afterwards). Action scenes, by contrast, are generally brief; the serial’s one long fistfight, a fairly dynamic sequence, is ruined by being chopped into bits and intercut with a static trial sequence; we never get to see more than a few fragments of the fight at a time. Custer’s action scenes are not only curtailed, but are also rather cheap-looking at times; cost-cutting is particularly noticeable during the battle in Blackpool in Chapter Four–a sequence which has actors repeatedly reacting to arrows thudding into doorways at them, but actually never shows the Indians who are firing off these shafts–save in mismatched stock-footage long shots of soldiers and braves tussling in the street.

Above: A shot from the severely fragmented Chapter Thirteen fight.

The attack on the wagon train in Chapter One and the longer Chapter Ten attack on the fort (a good sequence, and one of the serial’s few protracted action scenes) also feature stock footage, but combine it pretty skillfully with new footage. The outlaw attack on the pay wagon in Chapter Eight consists entirely of new footage; it’s energetic, but is staged and edited in such chaotic fashion that it’s hard to follow the action. The first phase of the Little Big Horn sequence in Chapters Fourteen also suffers from this problem, but the battle’s conclusion in Chapter Fifteen–with Custer and his men standing at bay in a tightening ring of mounted Indian attackers–is pretty well-done, as is the final gunfight between Cardigan and Blade that follows close on the Last Stand’s heels. The serial’s most memorable action scene, however, is the attack on the Trent’s wagon at the end of Chapter One, which has stuntmen Yakima Canutt and Ken Cooper (doubling Rex Lease and Chief Thundercloud) fighting on a team of horses and then falling beneath them–although this stunning piece of stuntwork is somewhat diminished by being filmed entirely in an extreme long shot.

Above left: The opponents in the fight atop the wagon team face off. Above right: Another faceoff, this one beginning the final gunfight between Reed Howes (left) and Rex Lease.

The wagon-team fight isn’t the only scene in Custer that’s marred by poor cinematography. Like most Weis-produced serials, Custer looks as if was filmed four or five years before its actual production date; cameraman Bert Longenecker and director Elmer Clifton film numerous action and dialogue scenes in single takes and rely heavily on medium and long shots, often giving the serial the photographed-stage-play look common to many early talkies. Longenecker and Clifton do use closeups, and other editing devices, to heighten the drama in some scenes–most notably in the various climactic scenes in the final chapter–which suggests that their primitive-looking handling of other scenes was due more to budgetary constraints than to any unfamiliarity with mid-1930s filming techniques.

Above: Rex Lease (buckskin shirt) introduces himself to the Trent outfit, in a take that holds at the pictured distance for over a full minute. The girl in the white shirt is Nancy Caswell; Josef Swickard is next to her, William Desmond next to him, and Bobby Nelson is standing beside Lease.

Custer’s first chapter ending–a wagon plummeting down a mountainside–is spectacular, while its second cliffhanger–a stock-footage buffalo stampede–is quite solid. Subsequent cliffhangers, however, tend to be weak and repetitious; no fewer than six chapters end with various characters about to be stabbed or tomahawked by Indians, while other episodes culminate with good guys being abruptly lassoed or dropped through trapdoors. Kit’s gun duel with the crooked Judge Hooker provides one of the better later cliffhangers, while the earlier chapter ending that has a blindfolded Kit stepping off a cliff is praiseworthy as well, being handled much more dramatically than a similar cliffhanger in the 1950s serial Son of Geronimo. This latter scene is also enhanced by camerawork that emphasizes the height of the cliff involved–one of the bluffs at Iverson’s Ranch, which serves as the serial’s principal location (and, incidentally, provides a more historically appropriate grassland-like backdrop for the titular Last Stand than the rocky canyons featured in some other cinematic versions of the Custer story).

Above left: The wagon plummets down the slope at the end of Chapter One. Above right: A barely visible Rex Lease is about to step from the top of that cliff at the end of Chapter Four.

The cast of Custer is almost entirely composed of silent-movie veterans, some of them broadly theatrical but others relatively down-to-earth. Leading man Rex Lease is one of the serial’s more natural performers, only sounding affected during his farewell to Red Fawn and a few other “emotional” scenes; for most of the serial he maintains a likably easy-going cheerfulness, switching to convincing toughness and grimness when confronting the villains. Former child actress Nancy Caswell makes a poised and rather aloofly pretty leading lady; she occasionally “registers” grief or glee so vividly as to give her facial expressions a slightly deranged look, but her performance–like Lease’s–is fairly restrained overall. Reed Howes is also restrained–almost to the point of blandness–as the villainous Blade, but does convey considerable self-assurance and hard-bitten shrewdness as he concocts his evil schemes.

Above, left-hand picture: Rex Lease and Nancy Caswell after another narrow escape. Above, right-hand picture: Reed Howes (holding knife) plots with henchman Robert Walker.

As the sweet-natured Red Fawn, the ever-lovable Dorothy Gulliver often seems blankly confused, looking as if she’s desperately trying to remember her dialogue (as in the Chapter Two teepee sequence). She isn’t helped by the writers (who let her character randomly fluctuate between Tonto-talk and perfectly fluent English); however, she does her best to give conviction to her unusual part, and often succeeds in displaying genuine emotion. Chief Thundercloud has one of his meatiest serial roles as the ruthless Young Wolf, and is extremely menacing in the part–intimidatingly towering over prospective victims and periodically flashing a ferocious smile that’s even more sinister than the angry frown he displays in other scenes; at times he hesitates quite a while between lines, but it’s hard to tell if this is due to acting awkwardness or merely intended as part of his depiction of his Indian character.

Above: Chief Thundercloud about to give someone a haircut, the hard way.

George Chesebro is outrageously and entertainingly hammy when his Lieutenant Roberts is angrily expressing (or, later, pretending to express) his hatred of the army that has cast him out, but is much more subtle when his character is sunk in fits of despair; his half-sad, half-angry, and disbelieving expression when he’s drummed out of the Seventh Cavalry in Chapter Three is particularly good, as is his slow but determined look as he finally realizes his degradation and shoves away his whisky bottle in Chapter Thirteen. Chesebro would never get such a multi-faceted role again, but he makes the absolute most of this one. The attractive and rather exotic-looking Lona Andre is also good as the tough-talking but warm-hearted Belle Meade, the woman who helps to redeem the Roberts character; she does an especially fine job in her bittersweet final scene.

Above: Lona Andre rebukes the brooding George Chesebro.

Old trouper William Farnum, as the fatherly Indian Agent Fitzpatrick, is by far the most self-consciously stagy member of the cast–delivering homespun Western-style lines (“By crackety!) in a studied and carefully articulated fashion that makes them less than convincing; however, as in his other serials, his archaic acting comes off as so sincere that it’s impossible to dislike him. Jack Mulhall is characterically brisk as Cavalry Lieutenant Cook; his character’s military position makes him slightly more reserved than in some of his other chapterplays, but his typical energetic warmth still shines through–particularly in his sympathetic interchanges with Chesebro’s Lieutenant Roberts. Milburn Morante is enjoyably colorful as the grizzled and savvy scout Buckskin, who basically functions as Rex Lease’s sidekick. George Morrell plays an emphatically Irish sergeant who frequently bickers with Morante’s character, repeatedly engaging him in an odd little verbal routine (“Who, sir?”–“You, sir!”) that sounds almost like the work of Dr. Seuss.

Above: Rex Lease (far left) and William Farnum (far right) react amusedly to the bantering of sergeant George Morrell and scout Milburn Morante.

Josef Swickard is dignified but also pompous and grumpy as Major Trent; the screenplay makes him seem more unpleasant than he otherwise would have by having him unconscionably attempt to keep the arrow (and, later, steal it) even after he knows that doing so will bring danger on everyone around him; despite this selfish action, he’s still presented as an admirable old fellow, a notable example of sloppy writing. Bobby Nelson is energetic and generally likable as Swickard’s adventurous grandson–except when he starts to cry or shriek childishly in the face of danger; he simply looks a little too old (fourteen) to get away with such reactions without embarrassment. Marty Joyce, as Nelson’s apparently half-witted companion Buzz, delivers a performance that’s only saved from obnoxiousness by being low-key; in each of his scenes, he rambles on incessantly in a flat monotone, delivering inane and apparently ad-libbed lines in stream-of-consciousness style. Weirdly, though Joyce is obviously a grown man, he’s repeatedly referred to as a “boy” and treated as a peer of Nelson’s character, making me wonder if the part was originally written for a child actor; if so, Joyce was apparently tossed into the role at the last minute and told to act like he was (mentally) six years old.

Above: Genuine boy Bobby Nelson instructs ersatz boy Marty Joyce in the art of bugling.

The imposing Frank McGlynn Jr. has relatively little to do as Custer, but actually manages to make the forever-controversial Colonel seem a little more three-dimensional than the impeccably noble or cartoonishly nasty Custers seen in other movies; his combination of swaggering joviality with peremptory gruffness makes his Custer seem like a man who could be both magnanimous and harsh, and who (like the historical officer) could win friends or make enemies with equal ease. Ruth Mix (Tom’s daughter) is given high billing but little screen time as Custer’s loyal wife; she handles her affectionate-but-worried interchanges with her cheerfully careless husband–and her reaction to his death–with plenty of feeling, yet avoids becoming too melodramatic.

Above: Frank McGlynn Jr. dismisses the worries of Ruth Mix.

Helen Gibson, star of the quasi-serial Hazards of Helen in the early silent era, is suitably lively in her brief turn as Calamity Jane, while a cast-against-type Ted Adams is genially swashbuckling in an even smaller turn as Buffalo Bill Cody. Allen Greer, on the other hand, is disappointing as Wild Bill Hickok; his steely glare is impressive, but his line delivery is far too flat and mild. Adams has a second and larger role as one of Reed Howes’ principal henchmen, playing this part with his usual shifty air. Robert Walker, however, is the most prominent member of Howes’ band; like his screen boss, he’s capably villainous, but a little bit bland. Carl Mathews, like Ted Adams, plays two roles–Custer’s Crow scout Curley, and the small but pivotal part of True Eagle; he’s all right in the former role, which is largely non-verbal, but as True Eagle his thick Oklahoma twang makes him sound painfully incongruous.

Most of the serial’s other Indians are genuine, though–or at least convincing imitators, like Iron Eyes Cody. Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull–who are extremely peripheral characters in the serial–are played by two Indian actors who are billed (respectively) as High Eagle and Howling Wolf; the aforementioned Cody plays a larger part as a fictional chief named Brown Fox, while John Big Tree has a miniscule but memorably scary bit as a wizened medicine man who almost makes a human sacrifice of Andy Joyce’s character. James Sheridan and former leading man Creighton Hale are henchmen, and Chick Davis is Young Wolf’s lieutenant Rain-in-the Face. Walter James is hammily pompous and shifty as the crooked Judge Hooker, Franklyn Farnum is the jittery Major Reno, Lafe McKee appears as Custer’s other aide-de-camp Benteen, William Desmond is seen briefly as a wagon-train boss, and Budd Buster and Cactus Mack both pop up as cavalry officers.

If the pacing, direction, scripting, plotting, and action in Custer’s Last Stand had measured up to the serial’s basic concept, it would have been one of the greatest chapterplays ever made–instead of the ponderous mess that it is. However, there’s enough salvageable material–strong performances, nice bits of stuntwork, interesting historical references, truly dramatic moments–buried in the wreckage of Custer to make the serial viewable (and, at times, even entertaining) for a Western or chapterplay buff.

Above: Frank McGlynn Jr. as Custer leads his troops towards Little Big Horn (to the accompaniment of the tune “Garry Owen”), in one of several stirring scenes that give glimpses of what Custer’s Last Stand could have been as a whole.

I would like to see what the budgets were for the three Stage & Screen serials. Someone claimed they were a ridiculously low $10,000, but someone else pointed out the film alone would have cost almost that much.

I had the dubious honor of seeing a few chapters of this serial in a theater in 1946. Later I saw a few chapters on line. Neither occasion changed my opinion of Custers Last Stand. Its rare that I have no favorable comment on a serial but this and another with William “Stage” Boyd, rate this distinction. As stated,this could have been very good. As presented , I give this no stars!

Ken, wait until you see YOUNG EAGLES and QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE.

Haha! Ken – please heed Pa’s sage advice. Six hours of my life irredeemably squandered. As the Queen of the Jungle said herself in chapter 12 – “Skip it!”. Too bad she didn’t say that in the first chapter.

Everyone except me says YOUNG EAGLES was the worst sound serial, I say QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE was much worse. At least in YE, it looked like a real jungle, and the feeling was the boys really were in deep trouble, but in QOTJ, anything that wasn’t stock footage, was filmed on a poorly decorated sound stage. A couple of chapters took place on a ship, and in the background was just a blank wall, no process screen or painting of the sea. It had to have had a budget that was a fraction of any other indi serial, maybe about $10,000 or so.

So true on all points. I actually found some of the cliffhangers in YE more terrifying than most because it was kids in jeopardy. There was some interesting location and animal footage, so it wasn’t a total loss, but a tedious schlep through the weeds nonetheless.

QOTJ was a curiosity because of the approach of matching obvious silent stock footage with new cheap sets and its mildly prurient overtones, but it is probably the worst serial ever made. IMDB lists some goofs I didn’t pick up, but I won’t be watching a second time to see them.

In general I have a real fondness for the serials of the early 30’s, probably because I saw them on TV as a kid in the 50’s, so I’m inclined to give a pass to many flaws, but these two just have too many.

Jerry–I don’t think the Chick Davis listed in the credits is actually the Chief Thunderbird who appeared in earlier serials at Universal and in Annie Oakley in 1935 as Sitting Bull. That Chief Thunderbird was born in 1866. I know that IMDB lists him as the same man as Chick Davis, but there must be some mistake. I am re-watching this serial and the man who plays Rain-in-the-Face is obviously much younger than Chief Thunderbird and at most bears only a passing resemblance to him. Chief Thunderbird would have been 70 years old in 1936. This man looks to be in his thirties. I think I know what happened after doing a bit of research on the internet. There was the elderly Cheyenne who acted under the name Chief Thunderbird whom we know from serials such as The Indians are Coming. There was also a Canadian Native American who wrestled professionally under the name Chief Thunderbird starting in the early 1930’s. My guess is that this wrestler, like many of his peers such as Mike Mazurki and Tor Johnson, dabbled in film acting, and as no one cared much, the credits of the two men were confused. To make a long post short–I don’t think Chick Davis was actually Chief Thunderbird.

Thanks very much for that correction, Old Serial Fan. I was skeptical about the Chief Thunderbird/Chick Davis listing on the Internet Movie Database, remembering Chief Thunderbird as looking much older in the earlier Battling With Buffalo Bill–but the Old Corral’s “Indians” page on Thunderbird also lists Chick Davis as Chief Thunderbird’s other name, so I went with it. However, that’s not the Old Corral’s fault, since I should have taken a look at the Thunderbird photos there instead of merely glimpsing at the name credit; there’s no way the ancient-looking Thunderbird was Rain-in-the-Face in this serial. I suspect that whoever did the Internet Movie Database listing saw that Chick Davis was listed as Thunderbird’s other name on the Old Corral, and decided that the unrelated Chick Davis in Custer must then be Chief Thunderbird. Anyway, thanks again for correcting me; I hate it when I find I’ve been carelessly sowing confusion.

Just re-watched this one, and my take is that this was more an erratic serial than an awful one. The cast was unexceptional, but decent, with hero Lease and villain Howes uncharismatic but okay. McGlynn did a credible job with Custer, who was presented realistically as a strong leader but recklessly over-confident. A few of the subplots were interesting. A few tedious. One thing I liked was the grubby realism, including the horse droppings on the dusty street. This one is way above the worst I’ve seen so far, like Queen of the Jungle or The Clutching Hand. **1/2 out of ***** (aside-the rah-rah 19th century marching songs made the really long intros palatable for me)

I seem to be one of the few that truly enjoyed this serial. Granted, some of its shortcomings are all too obvious (limited budget, dated camera work, sloppy plotting, etc) but it also has many moments of drama and emotion generally lacking in the more popular, action-oriented productions. I wouldn’t trade George Chesebro’s scenes for a hundred fistfights and stunts, no matter how expertly performed, and I also liked the work of Lona Andre and Dorothy Gulliver in giving a depth of feeling to their roles.

The film makers didn’t fully succeed here, not by a long shot, but at least they tried for something more than the run-of-the-mill, and I think the effort deserves a little more respect.

Here’s a detailed amount of information on the actor whose name always appeared as Chief Thundercloud:

____________

http://www.b-westerns.com/chief3.htm

____________

I assume it is not incorrect, at least intentionally. It seems to explain many things.

Richard