May 26th, 1907 — June 11th, 1979

Above: A publicity portrait of John Wayne from his third serial, The Three Musketeers (Mascot, 1933).

Long before he became one of Hollywood’s biggest and most enduring stars, John Wayne played the hero in three of Nat Levine’s Mascot Pictures serials; although his famous screen personality was not yet fully developed during his chapterplay years, it was already quite strong enough to make him one of Mascot’s best leading men. In his serials (as in his later features), he could be appealingly cheerful or intimidatingly tough, and conveyed both cheerfulness and toughness in strong but very natural style. At Mascot, this naturalness made him come off as the indomitable, sturdily sane anchor of each of his chapterplays, a welcome counterweight to the flamboyantly theatrical stage and silent-film players who regularly appeared in the studio’s serials; his rugged athleticism also suited him ideally in the non-stop action scenes that were another hallmark of Mascot’s chapterplays.

John Wayne was born Marion Robert Morrison in Winterset, Iowa, the son of a pharmacist; when he was about eight years old, his family moved to a farm in rural California, but soon relocated to the Los Angeles suburb of Glendale, where his father returned to the pharmacy business. Young Morrison spent the rest of his childhood in Glendale–where he acquired the nickname of “Duke,” gained his first acting experience in high-school plays, and distinguished himself on the high-school football team. In 1925, he went to the University of Southern California on a football scholarship, and in 1926 took a summer job as a prop man at Fox, where he began a long association with director John Ford; before long, he also started doing extra work and bit parts at Fox and other studios. An injury cost him his USC football scholarship, and he ultimately left college to work full-time at Fox; he spent most of the years 1927 through 1929 there, serving as a prop man, small-part actor, stuntman, and all-around handyman. In 1929, director Raoul Walsh decided that “Duke” Morrison was the fresh face he wanted to star in the Fox pioneer epic The Big Trail; the studio, encouraged by Ford, approved the choice and redubbed Morrison “John Wayne” for the occasion. However, natural, technical, and economic factors combined to make The Big Trail (released in 1930) an expensive flop, and Wayne’s newborn starring career seemingly flopped with it; Fox canceled the production of two already-announced Wayne vehicles, abandoned any idea of promoting him further, and let him go after co-starring him in a pair of medium-budgeted films, Girls Demand Excitement and Three Girls Lost.

After leaving Fox, Wayne signed a half-year contract with Columbia; he launched his stay there with a starring role in the 1931 drama Arizona, but was subsequently relegated to supporting parts, in the Jack Holt vehicle Maker of Men and a trio of B-westerns (one with Buck Jones, two with Tim McCoy). He returned to leading parts at his next Hollywood landing place–Mascot Pictures, where he starred in the 1932 serial The Shadow of the Eagle; this colorful but incoherently-plotted outing cast him as carnival stunt pilot Craig McCoy–who, aided by a trio of sideshow sidekicks (a midget, a strongman, and a ventriloquist) defended carnival boss Nathan Gregory (Edward Hearn) and his daughter Jean (Dorothy Gulliver) against a ruthless board of airplane-factory executives and a mysterious airborne criminal called the Eagle, who was trying to frame Gregory (a former flying ace) for crimes against said executives. Though surrounded by plot confusions, hammy co-stars (particularly Hearn), and scene-stealing sidekicks, Wayne held a steady acting course throughout Eagle, and never seemed overwhelmed by either the script or the performances of his supporting cast; he delivered his lines with low-key but commanding sincerity, and rushed into chases and fights with exuberant energy. One of his regular opponents in these fights, ace stuntman Yakima Canutt, would become one of Wayne’s best friends and most important mentors, following their first meeting on the set of Eagle.

Above: John Wayne takes off after an Eagle suspect in The Shadow of the Eagle (Mascot, 1932).

Above: John Wayne and strongman Ivan Linow overpower Lloyd Whitlock in The Shadow of the Eagle.

Before 1932 was over, Wayne had followed Shadow of the Eagle with a second Mascot serial, The Hurricane Express, in which he played a heroic young pilot named Larry Baker. In the serial’s first chapter, Baker’s engineer father was killed in a train wreck orchestrated by a sinister railway saboteur known only as the Wrecker; Larry then set out to unmask the villain and avenge this death–but, in order to do so, had to repeatedly fight the Wrecker’s henchmen on the rails, on the roads, and in the air. Filmed on striking railroad locations, filled with varied action, and blessed by a fairly logical plot, Hurricane Express was Wayne’s best serial (and one of Mascot’s best as well); it not only gave him an extended physical workout during its numerous action sequences, but also gave him some chances to flex his acting muscles. His reaction to his father’s death was unusually angry and violent for a serial hero, almost frightening in its straightforward ferocity–and, unlike most chapterplay protagonists, he never seemed to forget about his parent’s demise; although he was pleasantly good-natured at many points in the serial, he invariably became grim and aggressive when confronting Wrecker suspects, and never failed to impart a suppressed rage to his oft-repeated line “The Wrecker…the man who murdered my father.”

Above: John Wayne accuses Matthew Betz of causing his father’s death in the wreck of The Hurricane Express (Mascot, 1932).

Above: It’s a battle royale atop a railyard platform in The Hurricane Express; John Wayne’s opponents are Ernie Adams (far left), Glenn Strange (grabbing Wayne’s leg), Lloyd Whitlock (grabbing Wayne’s arm), Charles King (behind Wayne), and Al Ferguson (getting punched by Wayne).

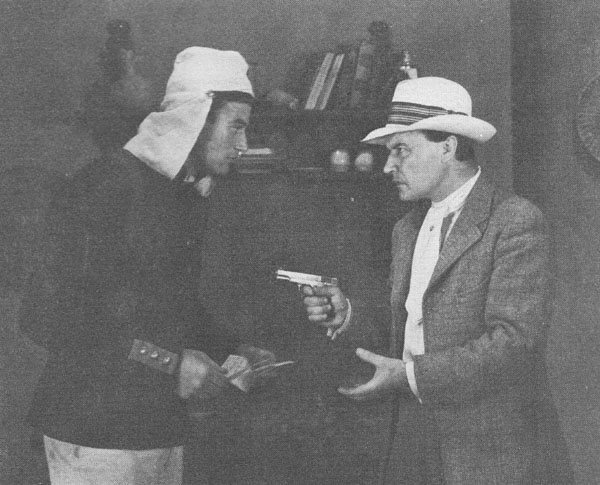

Now established as a viable matinee hero, thanks to his serial work, Wayne landed a B-western series (produced by Leon Schlesinger for Warner Brothers) in 1932; this series numbered six films in all, and lasted into 1933. In between his Schlesinger features, he played small parts in A-films at Paramount and Warners, starred in a romantic comedy (His Private Secretary) for independent producer Sam Katzman–and made his third and final serial, The Three Musketeers (Mascot, 1933). Once again he was cast as a pilot–Army flyer Tom Wayne, attached to the American Embassy in Paris–and once again he was pitted against a mystery villain–El Shaitan, a North African revolutionary leader waging war against the French Foreign Legion. When Legion officer Armand Corday (Lon Chaney Jr.), the brother of Wayne’s fiancée (Ruth Hall) and a reluctant member of El Shaitan’s “Devil’s Circle” group, used the unwitting Wayne’s plane to smuggle weapons to the Devil’s Circle, Wayne found himself wanted by the Legion on gun-running charges–and, to make matters worse, was also framed for Armand’s murder. However, a trio of adventurous Legionnaires (the “Musketeers” of the title), whom Wayne had previously saved from El Shaitan’s men, helped him to prove his innocence and unmask the real wrongdoer. An infectiously lively and action-packed chapterplay, Musketeers was marred by a few typical Mascot plot holes but was great fun overall; Wayne, who shared heroics with the three colorful Musketeers (Jack Mulhall, Raymond Hatton, and Francis X. Bushman Jr.), didn’t receive quite as much screen time as he had in his previous two serials, but was still definitely presented as the principal protagonist–and delivered another solid performance. He was likably jaunty and easygoing when interacting with the breezy Musketeers, calm and understated when confronting emphatically stagy antagonists like Robert Frazer and Gordon DeMain, fiercely determined when hunting for El Shaitan, and resolutely vigorous during action scenes.

Above: John Wayne and Ruth Hall bid a cheerful farewell to Francis X. Bushman Jr. in The Three Musketeers (Mascot, 1933).

Above: John Wayne seems unperturbed by the scowling threats of Robert Frazer in The Three Musketeers.

After finishing his B-western series for Schlesinger in 1933, Wayne began a new series of B-westerns for producer Paul Malvern, who released the films through Monogram; sparked by the stuntwork of Wayne and Yakima Canutt, this series proved popular in spite of very low budgets, and lasted through 1934 and into 1935. In the latter year, Malvern brought his production setup into the newly-formed Republic Pictures (which also absorbed Mascot); Wayne, now backed by greatly improved production values, continued as a B-western star at the new studio. When Malvern pulled out of Republic in 1936, Wayne moved with him to Universal, where he starred in a 1936-1937 series of Universal sports and adventure B-films; he then did a single upscale B-western (Born to the West) for Paramount before going back to Republic in 1938. He spent that year and part of the next one starring in Republic’s popular “Three Mesquiteers” B-westerns–and then, in 1939, made a return to A-pictures, when John Ford and producer Walter Wanger borrowed him from Republic and starred him in United Artists’ Stagecoach. Unlike The Big Trail ten years earlier, this film proved successful, and permanently removed Wayne from the B-movie and serial realm; though he officially stayed on the Republic roster until 1952, the studio restructured his contract to allow him to do extensive work for other companies, and featured him exclusively as an A-film star in their own films. Wayne’s subsequent career is too well-known to require any year-by-year recounting (even if there was room for it here); he steadily gained Hollywood prominence during the 1940s, and by the 1950s had become a top-ranking movie star. He retained his mega-star status throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, making his final screen bow in The Shootist, in 1976; he died of cancer in Los Angeles three years later, but remains one of America’s best-remembered actors to this day.

Not even the most diehard serial fan would try to pretend that John Wayne’s chapterplays were his most notable screen work, but they did play an important and often overlooked role in his overall career, firmly establishing him as a screen action star when he was in danger of sinking into film oblivion after the failure of The Big Trail, and paving the way for his B-western stardom–which, in turn, kept him afloat as a leading man until Ford gave him another chance in A-pictures. From the serial buff’s standpoint, however, Wayne’s serials were more than just career stepping-stones; they were entertaining chapterplays made additionally entertaining by their star–a hero whose unflappable ruggedness and quiet self-assurance was ideally suited to the wild and woolly Mascot milieu.

Above: John Wayne makes his second and successful entrance on the A-movie scene in Stagecoach (United Artists, 1939)–and makes his exit from the B-film and serial world.

Acknowledgements: Scott Eyman’s John Wayne: The Life and Legend (Simon and Schuster, 2014) provided me with much of the information in this article; other sources include the Old Corral’s page on Wayne’s 1930s B-westerns, The Complete Films of John Wayne (Citadel Press, 1983), by Boris and Steve Zmijewsky and Mark Ricci, and message-board posts by Ed Hulse about The Big Trail.