February 7th, 1919 — December 14th, 1989

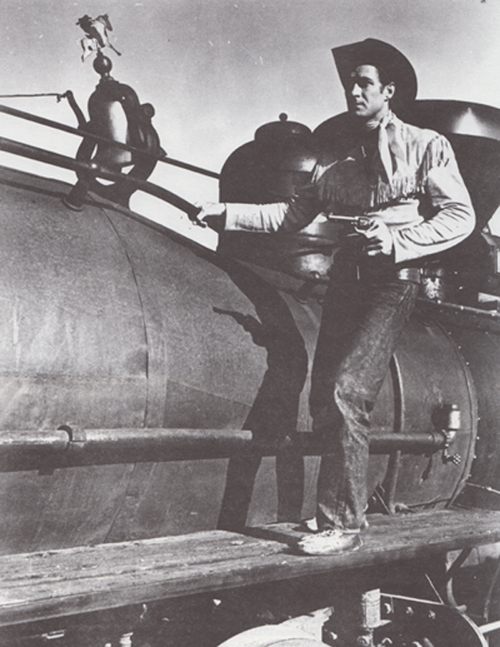

Above: Jock Mahoney in a still from his second serial, Roar of the Iron Horse (Columbia, 1951).

Ace stuntman Jock Mahoney was one of the only prominent members of his profession who managed to become a screen action hero in his own right. His vigorous but graceful athleticism has been repeatedly (and accurately) compared to that of a cat; this feline quality extended to his acting style, which was both quietly affable and quietly intimidating. Even in his most friendly and easygoing moments, he conveyed a catlike caginess and watchfulness that made it seem as if he was perpetually poised to spring into violent action. Though he’s best-remembered as a feature-film and television star, Mahoney received some of his earliest starring showcases in movie serials, top-lining a trio of cliffhangers–one strong, one weak, one middling–for Columbia serial producer Sam Katzman during the early 1950s.

Jacques Joseph O’Mahoney was born in Chicago, and spent the bulk of his childhood in Davenport, Iowa. During his school years, he devoted time to both theatricals and sports–specifically, gymnastics, track, basketball, football, and swimming; his sporting achievements ultimately won him an athletic scholarship to the University of Iowa. However, he dropped out of college in his second year (1940) and headed for California, hoping to launch an acting career; he did win some movie stand-in assignments, but spent most of the early 1940s as (successively) a lifeguard and swimming instructor at the Los Angeles Aviation Club, an aviation student, and a flight instructor, before joining the Marines in 1943 to train as a fighter pilot (his training and World War Two concluded around the same time, so he never actually saw wartime action). After receiving his discharge he returned to Los Angeles, where he took up horse-breeding but soon re-entered the movie business again–supplying Columbia Pictures’ B-western producers with horses, providing some of their actors with equestrian training, and playing minor henchmen roles for the studio.

From background “action heavy” to stuntman was one small step, and before 1946 was out Mahoney had taken that step; one of his earliest stunting assignments came in the disappointing medieval serial Son of the Guardsman (Columbia, 1946), in which he performed a couple of leaps and falls for star Robert Shaw (not the British actor). This chapterplay also gave Mahoney one of his first speaking roles; he appeared in the background of multiple scenes as Captain Kenley, the aide-de-camp of medieval baron Lord Markham (Wheeler Oakman), and periodically got to make reports to Markham or verbally acknowledge the nobleman’s orders.

Above: Wheeler Oakman (center) and Jock Mahoney confer in Son of the Guardsman (Columbia, 1946).

Recognizing Mahoney’s outstanding athletic prowess, Columbia kept him on frequent stuntman retainer during the remaining years of the 1940s, regularly using him to double B-western star Charles Starrett and A-Western star Randolph Scott; he also began to receive increasingly larger acting roles in Starrett and Scott’s films, while performing additional stunt work at studios such as Fox, Warner Brothers, and Republic. In 1950, Columbia gave him his first official leading role, in the uneven and pedestrian serial Cody of the Pony Express. The title part was played by former child star Dickie Moore, while Mahoney was cast as Jim Archer, an army lieutenant assigned to investigate outlaw attacks on the Pony Express. Though Mahoney received top-billing (as “Jock O’Mahoney”) in Cody, he was relegated to the serial’s assistant-hero spot, regularly supporting Moore in clashes with the villains, but only occasionally getting a chance to perform any individual bits of heroic action. On these rare occasions (as when he calmly but alertly faced down a professional gunfighter in Chapter Fourteen), Mahoney displayed so much more screen presence than his low-key co-star Moore that most viewers were probably left wondering why he hadn’t been given the serial’s leading role.

Above: Jock Mahoney confronts gunfighter Rusty Wescoatt, as Baruch Lumet watches in Cody of the Pony Express (Columbia, 1950).

Above: Dickie Moore and Jock Mahoney discuss a clue in Cody of the Pony Express (Columbia, 1950).

Later in 1950, Mahoney played his first real heroic role in the unusual Western The Kangaroo Kid–a British/American/Australian co-production–and starred in the Columbia B-comedy Hoedown; Columbia also assigned him several more supporting roles in their Charles Starrett B-westerns, hoping to pave the way for his eventual takeover of the Durango Kid series, once the aging Starrett retired. In 1951, Mahoney was again given top billing (still under the O’Mahoney name) in another Columbia serial, Columbia’s Roar of the Iron Horse; this time, his character was just as prominent in the action as his name was in the credits. As a railroad troubleshooter (and undercover marshal) named Jim Grant, he held center stage throughout the serial, capably battling two separate groups of railroad-raiding outlaws. Iron Horse was one of Columbia’s very best post-war chapterplays, thanks in part to smooth pacing and plotting, a good cast, the strategic use of a real train, and strong Nevada location work. Mahoney’s efforts also contributed notably to Iron Horse’s success; he not only performed many of his own stunts–greatly enhancing and enlivening the serial’s action scenes–but also delivered a commanding performance. He switched (with startling suddenness) from disarming affability to steely authoritativeness during confrontations with the villains, pondered plans with convincing shrewdness and thoughtfulness, and gave an amusing touch of dryly deadpan humor to his interactions with garrulous sidekick William Fawcett.

Above: Hal Landon and Jock Mahoney on the alert in Roar of the Iron Horse (Columbia, 1951).

Above: Mahoney literally leaps into action in Roar of the Iron Horse.

Shortly after making Roar of the Iron Horse, Mahoney adopted the new screen name of “Jack Mahoney” and signed with Gene Autry’s television production company “Flying A” to star in the TV series The Range Rider. This action-packed show, deliberately designed to showcase Mahoney’s stuntman abilities, ran for two seasons (from 1951 to 1953). In between Range Rider filming sessions, Mahoney made another set of appearances in Columbia’s final batch of Charles Starrett B-westerns, playing what amounted to co-starring roles; however, Columbia’s plan to anoint him as Starrett’s successor ultimately came to nothing–since, by 1952 (the year of Starrett’s retirement), Western television shows had thoroughly undercut the market for B-westerns, making it pointless for Columbia to launch a new series of cowboy movies. Mahoney did star in one more Columbia serial, however, after finishing the second and last season of Range Rider. This serial was Gunfighters of the Northwest (1953), which starred him (this time under his new “Jack Mahoney” moniker) as Mountie sergeant Joe Ward, who set out to track down a band of bandit-revolutionaries known as the “White Horse Rebels.” Stronger than Cody of the Pony Express, but much weaker than Roar of the Iron Horse, Gunfighters featured a first-rate cast and terrific location work, but was marred by truncated action scenes and by a poorly-constructed storyline that placed far too much of its emphasis on the White Horse Rebels’ internecine squabbles. After the first two or three chapters, Mahoney was given almost no chance to perform the lively stunts that had marked Iron Horse, and was also frequently forced to the sidelines in order to make room for the Rebels’ seemingly endless feud with renegade henchman Anders (Zon Murray). Still, Mahoney did receive some good scenes in Gunfighters; his good-natured bantering with chipper sidekick Tommy Farrell, his bitterly angry reaction to Farrell’s death, his friendly but wary conversations with seemingly shady leading lady Phyllis Coates, and his crafty undercover pose as a seedy trapper all effectively showcased his acting talent.

Above: Clayton Moore and an out-of-uniform Jock Mahoney find important evidence on a fallen heavy in Gunfighters of the Northwest (Columbia, 1953).

Above: Mahoney slugs it out with a White Horse Rebel in Gunfighters of the Northwest.

Mahoney was originally slated to star in a fourth serial, Columbia’s Riding with Buffalo Bill; however, this outing was designed to rely almost entirely on stock footage from earlier serials–and the costumes from said serials proved too small for for the six-foot-four Mahoney, necessitating a casting change. Mahoney left Katzman’s Columbia serial unit behind for good, and moved on to other things; after starring in the 1954 A-western Overland Pacific for producer Edward Small and making several guest-star appearances on The Loretta Young Show, he signed with Universal Pictures. There, he starred in numerous A-westerns, a couple of dramas, and the science-fiction film The Land Unknown, and also played major supporting roles in the features Battle Hymn and A Time to Love and a Time to Die. In 1958 he left Universal to star in the offbeat and excellent Western TV series Yancy Derringer, which developed a strong following but was abruptly canceled (the victim of a dispute between its producers and the network) after a single season. Mahoney then guested on several other TV series (Rawhide, Laramie), and also journeyed to Africa to play the villain in producer Sy Weintraub’s 1960 feature Tarzan the Magnificent; Weintraub was so impressed with Mahoney’s performance in this film that he subsequently cast him as Tarzan himself in Tarzan Goes to India and Tarzan’s Three Challenges. Both movies were successful, but the second one (released in 1963) had terrible personal effects on Mahoney; he almost died of pneumonia, dysentery, malaria, and dengue fever while filming Challenges on location in Thailand, and never fully recovered from the effects of these diseases. After starring in a handful of independently-produced action films in the mid-1960s, he ended his leading-man career and took up horse-breeding again; however, he continued to work steadily on television and in occasional movies during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Also in the 1970s, he began to make contact with his many fans, appearing at various Western movie conventions. He suffered a stroke in 1973, but returned to the screen and to the convention trail by the middle of the decade; he sporadically accepted film and TV assignments until 1985, when he retired from acting (not long after receiving a special stuntman’s award). He spent his last years in Poulsbo, Washington, and died (from the combined effects of a car accident and a second stroke) in the hospital of the nearby town of Bremerton.

Jock Mahoney retains a strong and well-deserved fan following to this day; most members of this following, however, know him for Range Rider, Yancy Derringer, his Universal features, and his Tarzan movies–and not for his more obscure movie serials. Similarly, chapterplay buffs often overlook him when putting together lists of the great serial heroes–partly because all three of his serials were made during the generally neglected postwar era, and partly because two of the three were decidedly indifferent in quality. Still, he gave his serials the benefit of the same physical presence and relaxed but commanding personality that he brought to his later and better-known starring vehicles; had he begun his chapterplay career earlier, or had he managed to land more serial vehicles of the quality of Roar of the Iron Horse, he’d undoubtedly have achieved cliffhanging fame on a level with that of Buster Crabbe, Tom Tyler, and other charismatic and athletic serial greats.

Above: Jock Mahoney atop the “iron horse” in Roar of the Iron Horse (Columbia, 1951).

Acknowledgements: The biographical information in this article was mostly derived from Gene Freese’s fine book Jock Mahoney: The Life and Films of a Hollywood Stuntman (McFarland, 2013). Robert Callaghan’s Jock Mahoney website and Neil Summer’s profile on Mahoney at the Western Clippings site were also helpful.