December 12th, 1904 — December 10, 1995

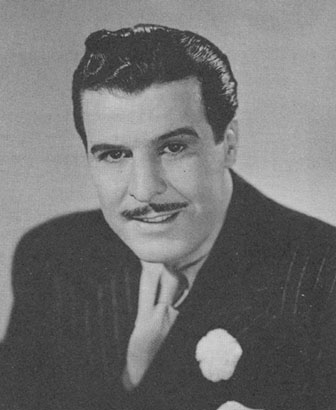

Above: A publicity portrait of George J. Lewis in the serial Federal Operator 99 (Republic, 1945).

Unlike most of the serial performers I’ve placed in the Character Actors section, George J. Lewis played co-starring roles far more often than supporting parts or bits. However, said co-starring roles were so variegated that it seems most appropriate to place him under the catch-all “character actor” designation; he portrayed heroes, brains heavies, sidekicks, and action heavies over the course of his distinguished serial career. Lewis handled each of these chapterplay character types in assured, convincing, and very effective fashion; in heroic parts, he balanced sober determination with likably cheerful enthusiasm–while in villainous roles he could be suavely dispassionate or coldly harsh and aggressive, depending on the type of heavy he was playing.

George Lewis was born in Guadalajara, Mexico, to a Mexican mother and an American father. The latter was an executive for an American typewriter company with a branch in Mexico, where the Lewis family lived until the 1910 Mexican Revolution forced them to relocate–first to Illinois, then to Brazil, and then (in 1913) to Wisconsin. The elder Lewis served in the Army during World War 1 and was for a time assigned to homefront duty in California, permanently settling there with his family after the war. His son began to pursue an acting career after finishing high school, working in West Coast theatrical stock companies before beginning his Hollywood career in 1923. Young George worked as a bit player and stunt double during his first two years in movies, but became a star after playing a leading role (a Jewish-American boxer at odds with his traditional-minded immigrant parents) in the prestigious Universal Pictures drama His People (1925). Following the success of this film, Universal signed Lewis to a contract, casting him in major parts in another drama called Devil’s Island and the comedy The Old Soak–and then, in 1926, assigning him his first top-billed role in a short called The Collegians; this title was the first in a series of over forty shorts, all of which starred Lewis as college athlete Ed Benson. The “Collegians” shorts would occupy most of Lewis’s acting schedule during the second half of the 1920s, although he did find time to play a few more co-starring roles in full-length Universal films like 13 Washington Square or Give and Take.

Lewis’s Universal contract expired in 1929 as the sound-film era dawned, and the studio chose not to renew it–probably because of Lewis’s very slight Spanish accent, which was practically indistinguishable, but which gave his dialogue delivery in talking films a sharp and precise sound that didn’t quite match with the All-American college-boy image he had developed during the silent era. In 1930, he signed a contract with the Fox Film Corporation, and began playing starring roles in a string of Spanish-language versions of big-budget Fox features (The Big Trail, Last of the Duanes) intended for the Latin-American market. This line of work began to play out for Lewis after a few years, as studios’ dubbing technology improved; he left Fox in 1932 and began working as a freelance actor. He starred in a few Mexican films, played supporting parts in a couple of American B-films, and (in 1933) made his first serial appearance in Mascot Pictures’ The Whispering Shadow. His role in this chapterplay was small, although pivotal; as Bud Foster, a young truck-driver and brother of the hero (Malcolm McGregor), he was shot and killed by hijackers in the first chapter–sending his brother off in pursuit of the criminal mastermind responsible for the hijacking in the ensuing chapters. Lewis played his role here very much in his chipper Collegians vein–eagerly offering to take over a potentially dangerous trucking run, and cheerily brushing aside fears of hijacking.

Above: Eddie Parker and George J. Lewis begin an ill-fated trucking run in The Whispering Shadow (Mascot, 1933).

Lewis almost immediately followed his Whispering Shadow turn with a leading role in the Mascot chapterplay The Wolf Dog (also 1933). As a young ship’s officer named Bob Whitlock, he helped the young owner of a shipping line (Frankie Darro) battle the villains trying to take it over–while also trying to keep the same villains from seizing his own invention, a militarily valuable ray machine; both Lewis and Darro were assisted by Rin Tin Tin Jr., as the titular canine. As an officer, an inventor, and a hero, Lewis was appropriately more serious and responsible in demeanor in Wolf Dog than he had been in Whispering Shadow, sharply barking out orders and racing after villains with grave determination. However, he was still quite effervescent when not engaged in serious matters–describing his invention with enthusiastic pride and very affably interacting with both his human and canine co-stars.

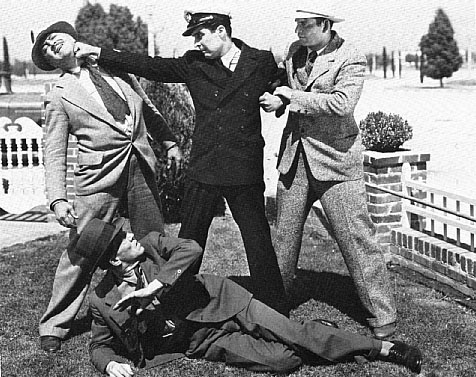

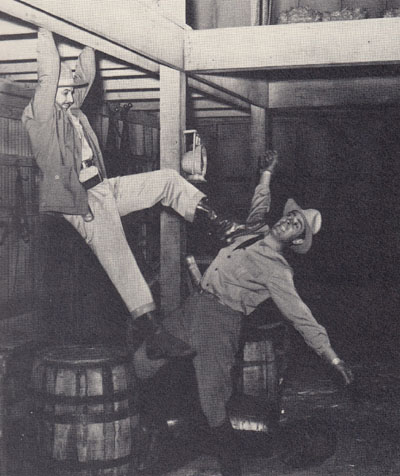

Above: George J. Lewis grapples with Gordon DeMain in The Wolf Dog (Mascot, 1933).

Above: An outnumbered George J. Lewis holds his own against the heavies in another scene from The Wolf Dog. Stanley Blystone is on the receiving end of Lewis’s straight right, Yakima Canutt is holding Lewis’s arm, and Tom London is on the ground.

Lewis appeared in several more B-films, Mexican productions, Hollywood Spanish-language features, and a few A-films before making his third and final Mascot serial, The Fighting Marines (1935). He was cast as a Marine Sergeant named Bill Schiller, the brother of the heroine (Anne Rutherford) and the inventor of a valuable new “gyro-compass.” Captured by a criminal called the Tiger Shark, who was determined to control the new invention, Schiller was rescued from the Shark’s island hideout by heroic fellow Marines Lawrence and McGowan (Grant Withers and Adrian Morris)–but was injured in the process, and then murdered in the hospital by a Tiger Shark henchman in Chapter Four. Though Lewis’s character in Marines was important to the plot, he spent much of his time offstage or wounded before getting killed off; Lewis made the most of his limited screen time, particularly in his fervent defiances of the villains (“If you fellas think you can buck the Marines and get away with it, you’re crazy”).

Above, from left to right: Grant Withers, Anne Rutherford, and George J. Lewis in The Fighting Marines (Mascot, 1935).

By 1936, Lewis realized his career was caught in a cul-de-sac; producers still tended to think of him as a clean-cut juvenile, but were no longer giving him starring roles–relegating him for the most part to bits or bland secondary lead parts. He therefore decided to leave Hollywood for a while and headed east to New York, where he began appearing in Broadway plays and on radio shows; he kept working principally on the East Coast from 1936 to 1940, only occasionally venturing back to California. Lewis worked assiduously to diversify his acting resume during this time, seeking out roles as (in his own words) “gangsters, villains, and really no-good characters.” Upon his return to Hollywood late in 1940, he found he had successfully proven himself a versatile actor, and soon began winning villain and character parts in B-films, serials, and (occasionally) A-films, particularly at RKO and Republic; these parts gradually increased in size as the 1940s wore on.

One of Lewis’s first notable heavy turns came in the chapterplay Gang Busters (Universal, 1942); as a vicious gangster named Mason, he figured prominently in the serial’s first three episodes, participating in several robberies and murders until he was identified by the police–at which point he seized the heroine as a hostage and tried to escape a police dragnet, only to die in a car crash. Lewis got to do some memorably confident sneering and angry snarling before his character met his demise–particularly during his doomed getaway in Chapter Three.

Above: George J. Lewis and Irene Hervey view oncoming police cars with very different emotions in Gang Busters (Universal, 1942).

Spy Smasher (1942), the first of Lewis’s many Republic serials, gave him a one-chapter villainous role as a Nazi agent who posed as a munitions plant official, smoothly showing a US Intelligence official over a warehouse that was really a secret spy base. He received more screen time in Republic’s next serial release, Perils of Nyoka (also 1942), but spent most of it in the background; he was cast as Batan, the lieutenant of villainous Arab tribal leader Cassib (Charles Middleton)–who was in turn the lieutenant of evil desert queen Vultura (Lorna Gray). As the henchman’s henchman, Lewis had fairly few lines, although he took part in chases, fights, and torture sessions in properly grim and sinister style.

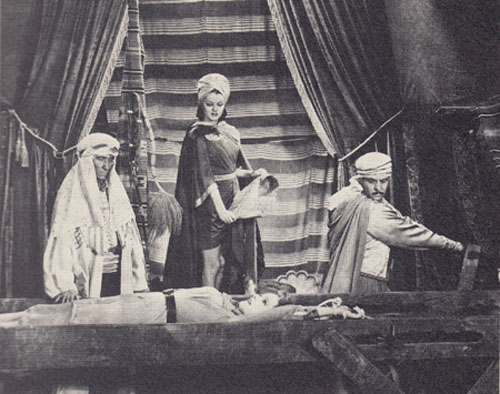

Above: George J. Lewis stretches heroine Kay Aldridge on the rack in an attempt to attain some information for Charles Middleton and Lorna Gray in Perils of Nyoka (Republic, 1942)

Lewis took his first major serial villain part in G-Men vs. the Black Dragon (Republic, 1943); as Lugo, one of the two leading henchmen of Japanese agent Haruchi (Nino Pipitone), he teamed with fellow-henchman Ranga (Noel Cravat) to lead a series of assaults on America’s wartime defenses, repeatedly battling G-man hero Rex Bennett (Rod Cameron) in the process. Lewis played his character with an intimidating air of icy rage; while he was always cold-bloodedly efficient when committing murder or sabotage, he also displayed a vicious, barely-restrained fury every time Lugo was crossed or thwarted by Bennett. This memorable combination of businesslike calm and savage anger would mark most of Lewis’s subsequent serial action-heavy turns.

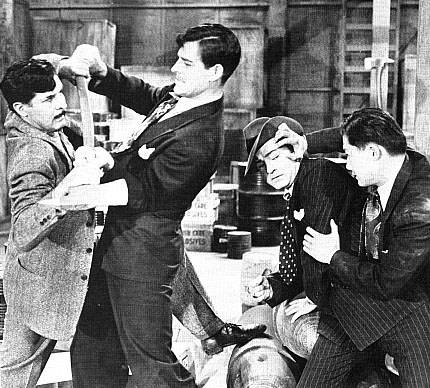

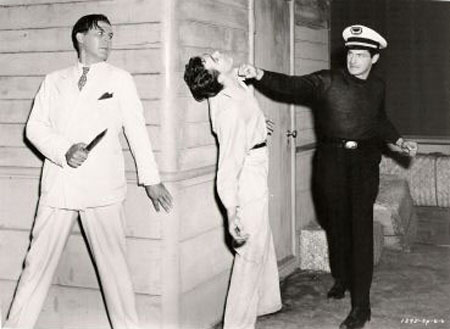

Above: George J. Lewis grapples over an axe with Rod Cameron, while Roland Got (far right) struggles with Noel Cravat in one of the dynamic fight scenes from G-Men vs. the Black Dragon (Republic, 1943).

Above, left to right: Nino Pipitone (center) tells Noel Cravat and George J. Lewis how he intends to use his pet raven to make off with some important papers in G-Men vs. the Black Dragon.

Lewis again played one-half of a team of a henchman team–an outlaw named Turner–in Daredevils of the West (Republic, 1943), pairing with William Haade to wreak havoc on a beleaguered frontier stage-line; he was a little less prominent here than in Black Dragon, but still took an active part in most of the serial’s evildoing–and played his part with the same icily furious air he had displayed in the preceding outing. Later in 1943, he ventured over to Columbia Pictures to appear in the chapterplay Batman; here, he was Burke, one member of a very large pack of recurring henchmen, and received comparatively few individual villainous moments–although he gave a distinctively harsh and nasty turn to his occasional lines.

Above: William Haade watches as George J. Lewis guns down a pair of (off-camera) unarmed Indians in Daredevils of the West (Republic, 1943).

Above: George J. Lewis and Jack Ingram grin evilly, mistakenly thinking they’ve just finished off Batman (Columbia, 1943) by knocking his car off the road.

Lewis was back at Republic for Secret Service in Darkest Africa (1943); this sequel to G-Men vs. the Black Dragon featured him in a single-episode bit as an Arab henchman named Kaba, who was shot after a fierce fistfight with Rod Cameron’s Rex Bennett. He was originally slated to play the action heavy in Republic’s The Masked Marvel (also 1943), but scheduling conflicts forced him to take a much smaller role as a crooked lawyer named Phillip Morton, who was killed off during a spectacular fight sequence that followed close on the heels of his first appearance.

Captain America (Republic, 1944) cast Lewis as Bart Matson, the henchman of a mad master criminal known as the Scarab (distinguished feature-film villain Lionel Atwill); this time out, Lewis was the sole recurring action heavy, and thus received more time in the villainous spotlight than in either G-Men vs. the Black Dragon or Daredevils of the West. Once again, he gave his character a chillingly vicious edge, glowering murderously and snapping harshly at the hero (Dick Purcell), the heroine (Lorna Gray), and the various scientists his boss had marked for elimination. His grimness played well off of the more suave villainy of Atwill, and he was able to hold his own in the menace department against the far better-known filmic heavy.

Above: George J. Lewis, in blatant disregard of the notice on the wall behind, prepares to incinerate the off-screen Captain America (Republic, 1944) with a deadly “firebolt” ray.

Above: George J. Lewis reports to Lionel Atwill in Captain America. John Davidson is in the background.

Lewis was again the sole action heavy in The Tiger Woman (Republic, 1944); as a jungle ruffian named Morgan, he handled almost all the dirty work for crooked oil-men LeRoy Mason and Crane Whitley, helping them in their attempts to destroy rival oil-company representative Allan Lane and white jungle queen Linda Stirling. Lewis played his character with his now-customary cold viciousness, and added a touch of arrogance to the part as well; he treated Mason and Whitley more like equals than like bosses throughout the serial, curtly arguing with them and criticizing their plans with a dismissive sneer.

Above: George J. Lewis temporarily bests Allan Lane during a fight scene in The Tiger Woman (Republic, 1944).

Above: Linda Stirling (as The Tiger Woman) and George J. Lewis.

Lewis took a brief hiatus from Republic serials to appear in the chapterplays The Desert Hawk (Columbia, 1944) and Raiders of Ghost City (Universal, 1944). In the former, he had a small non-villainous role as the stalwart captain of an Emir’s bodyguard, while in the latter he played an inactive but fairly prominent role as a 19th-century Prussian spy named Friedrich Lentz, the code clerk for master spies Lionel Atwill and Virginia Christine; his main function here was to tersely reel off deciphered messages and assist Atwill and Christine in verbally reminding the viewers of the villains’ objective (which was the purchase of Alaska with gold stolen from American mines).

Above: Lionel Atwill and Virginia Christine watch as George J. Lewis copies down an important message in Raiders of Ghost City (Universal, 1944).

Haunted Harbor (Republic, 1944), featured Lewis as Dranga, a South Seas storekeeper who pretended to friendship with sea-captain hero Kane Richmond–but secretly kept villainous gold smuggler Roy Barcroft informed of Richmond’s movements. Though his character was unmasked by Richmond’s and killed off by Barcroft’s at the serial’s halfway point, Lewis received many good scenes before this exit–and handled his sly and subtle character just as skillfully as the more straightforwardly nasty heavies he had played in his earlier Republic serials, continually shifting between feigned affability, crafty thoughtfulness, and repressed irritation when taking part in the good guys’ strategizing sessions.

Above: Kane Richmond slugs Johnny Daheim in Haunted Harbor (Republic, 1944), while a lurking George J. Lewis waits to take a hand in the fight.

Black Arrow (Columbia, 1944) cast Lewis as a hostile Indian warrior named Snake-that-Walks, who seized the tribal leadership from Black Arrow (Robert Scott) after the latter refused to start a war with the white settlers, and then bedeviled Black Arrow and his Indian-agent ally Tom Whitney (Charles Middleton) at regular intervals, eventually allying himself with outlaws led by smooth profiteer Jake Jackson (Kenneth MacDonald). Lewis spent most of his time on the peripheries of the action in Black Arrow, but brought a suitable mixture of stoicism and ferocity to his part; he departed the serial in Chapter Thirteen, after losing a knife duel with Black Arrow and then being killed by one of his fellow-tribesmen while treacherously trying stab the hero in the back.

Above, left to right: George J. Lewis, Chief Thundercloud, and Robert Scott in Black Arrow (Columbia, 1944).

Zorro’s Black Whip (Republic, 1944) temporarily returned Lewis to serial heroism; as an undercover frontier lawman named Vic Gordon, he took on a well-organized outlaw band with the aid of a masked avenger known as the Black Whip–who was actually frontier newspaper editress Barbara Meredith (Linda Stirling). Lewis shared screen time pretty equally with his female co-star in Black Whip; he got to perform plenty of heroics and performed them quite well. Though much more solemn and much less buoyant than he had been in The Wolf Dog eleven years earlier, he again balanced grave authoritativeness and geniality to good effect–confronting heavies with imposing sternness, but relaxing into quiet cheerfulness when conferring with the heroine.

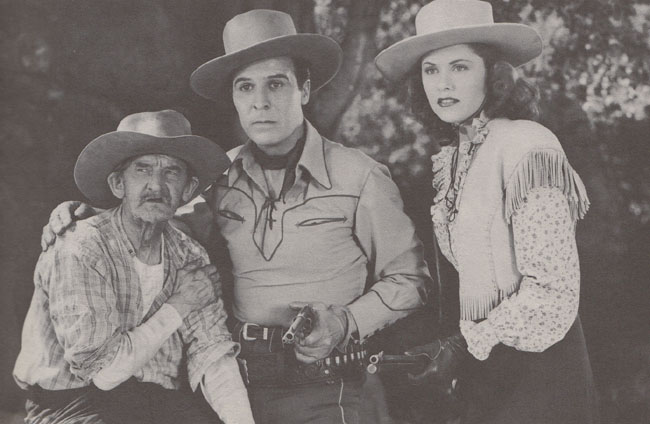

Above: Si Jenks, George J. Lewis, and Linda Stirling in Zorro’s Black Whip (Republic, 1944).

Above: Linda Stirling brings good news to a wrongfully incarcerated George J. Lewis in Zorro’s Black Whip.

After appearing in a total of fifteen serials from 1942 to 1944, Lewis scaled back considerably on his chapterplay workload during the remaining years of the 1940s, concentrating instead on feature-film parts (chiefly turns as heavies, Mexican officials, or Indians in B-westerns for Monogram, Republic, and Columbia); he would only appear would in six more serials over the next five years. The first of these was Federal Operator 99, which cast him as sophisticated master criminal Jim Belmont–who played Beethoven pieces on the piano when he wasn’t planning and executing intricate robberies, or trying to rid himself of tenacious G-man Jerry Blake (Marten Lamont). Lewis, who would later refer to the Belmont part as his favorite serial role, did a terrific job as the urbane mastermind; he explained plans to his associates with a smugly condescending air, gave a suitably dry and sarcastic turn to Belmont’s cynically witty dialogue (“It’s what I would call poetic justice–if I believed in justice”), met setbacks with unflappable calm, and performed acts of villainy with an emotionally detached air just as frightening as the ferocity that had marked most of his henchman characters.

Above: George J. Lewis confronts Marten Lamont in Federal Operator 99 (Republic, 1945).

Above: George J. Lewis enjoys a musical interlude while henchmen LeRoy Mason (left) and Hal Taliaferro watch in Federal Operator 99.

The Phantom Rider (Republic, 1946) gave Lewis an active assistant-hero role as Blue Feather, the college-educated son of a reservation Indian chief. His character’s efforts to organize an Indian police force (in order to suppress an outlaw gang using the reservation as a hideout) drove the serial’s action throughout its twelve chapters–with the outlaws’ secret leader (LeRoy Mason) doing his best to crush the police project and local doctor Jim Sterling (Robert Kent) doing his best to foster it (assuming the guise of a legendary Indian spirit for the purpose). Lewis’s talent for being both serious and good-natured fit his Rider role well; he made Blue Feather sound properly concerned and indignant about the outlaw situation, yet retained more than enough cordiality to keep the character from ever seeming stuffily self-righteous.

Above: Robert Kent and George J. Lewis in The Phantom Rider (Republic, 1946).

Above: Chief Thundercloud (far left) and George J. Lewis are confronted by outlaw Kenne Duncan and a band of Indian renegades in The Phantom Rider. Bob Wilke is behind Duncan.

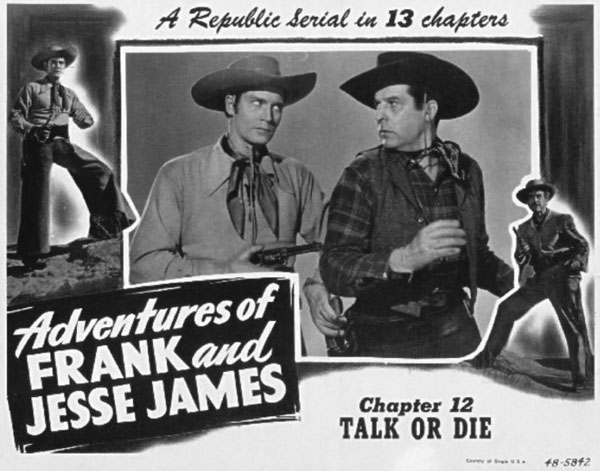

Lewis didn’t make another chapterplay until 1948, when he took his last serial action heavy role in Adventures of Frank and Jesse James (Republic, 1948); he played a pragmatic outlaw named Rafe Henley, who aided a crooked mining engineer (John Crawford) in his efforts to seize control of a profitable gold mine. Lewis’s performance here was a little more laid-back and less tensely aggressive than his henchman characterizations in earlier Republic serials–but was just as coldly and sneeringly nasty as those earlier characterizations had been.

Above: Clayton Moore gets the drop on George J. Lewis in a lobby card for Adventures of Frank and Jesse James (Republic, 1948).

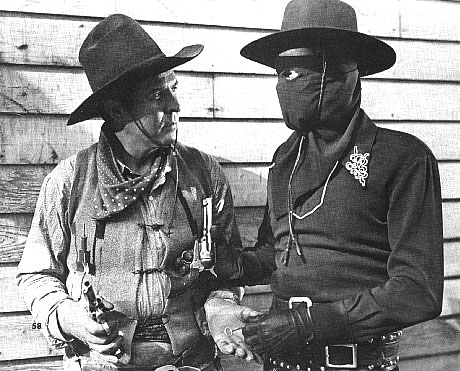

Ghost of Zorro (Republic, 1949) cast Lewis as the sidekick of the same leading man (Clayton Moore) that he had opposed the year previously in Adventures of Frank and Jesse James. Lewis’s Moccasin, the faithful Indian retainer of the Vega family, helped Moore’s Ken Mason–the last scion of that family–to fight Western banditry in the Zorro guise originally created by Don Diego Vega (the grandfather of Moore’s character). Lewis maintained an good balance of toughness and cheerful zeal throughout Ghost, and did an excellent job of gravely recounting the Vega family history in the first episode.

Above: George J. Lewis and the masked Clayton Moore in Ghost of Zorro (Republic, 1949).

Above: George J. Lewis doffs Zorro’s mask, after using it and the Zorro costume to pull Clayton Moore out of a tough spot in Ghost of Zorro.

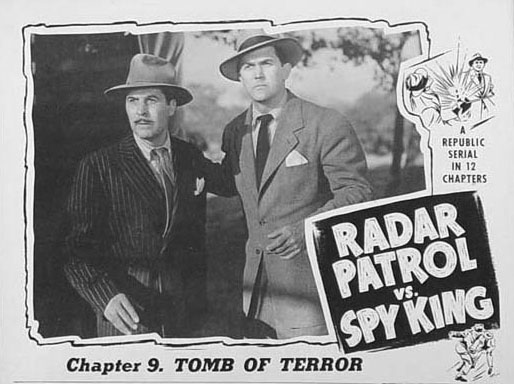

Radar Patrol vs. Spy King (Republic, 1949), was Lewis’s last Republic serial; he was cast as a Mexican police detective named Manuel Agura–who helped American secret service agent Chris Calvert (Kirk Alyn) combat spies along the Southwestern US border. Lewis turned in the most uniformly serious of his non-villainous serial performances here, giving his character a brusque and down-to-earth demeanor befitting a law-enforcement officer; the gruffly disgusted way in which he reacted to the villains’ activities was quietly amusing at times. However, he had disappointingly little screen time in Spy King, despite high billing; his character accompanied Alyn’s during a few clashes with the spies, but spent most of his time standing by at the good guys’ radar-station base while Alyn and leading lady Jean Dean went out on investigative missions.

Above: George J. Lewis and Kirk Alyn in Radar Patrol vs. Spy King (Republic, 1949).

Lewis’s final serial was a Columbia chapterplay, 1950’s Cody of the Pony Express. He played the brains heavy for the second and last time in his chapterplay career–specifically, a lawyer named Mort Black, who was commissioned to take over the Pony Express by a monopolistic Eastern syndicate, but who ran into constant opposition from young Express rider Bill Cody (Dickie Moore) and cavalry officer Jim Archer (Jock Mahoney). Black posed as a respectable pillar of the community throughout most of Cody, giving Lewis many good opportunities to hypocritically feign concern over his own henchmen’s depredations or dignifiedly proclaim his devotion to law and order. He entertainingly reverted to his more characteristic villainous manner when closeted with his henchmen or when dealing with pompous and impatient syndicate emissaries–sharply and angrily rebuking the former, and scarcely veiling his contemptuous annoyance with the latter.

Above: George J. Lewis affirms his support of law and order after being elected town judge in Cody of the Pony Express (Columbia, 1950), as Jack Low (standing) and Baruch Lumet (seated) watch.

Above: George J. Lewis plots with Jack Ingram (left) and Rick Vallin in Cody of the Pony Express.

Lewis continued to work in B-westerns during the 1950s, and also played many good guys and bad guys on Western TV shows like The Range Rider, The Gene Autry Show, and The Lone Ranger. Beginning in 1950, he also began increasing his A-feature appearances, thanks to a personal friendship with Alan Ladd; the star found good-sized villainous or character parts for Lewis in many of his vehicles, among them Captain Carey USA, Desert Legion, and Hell on Frisco Bay. However, Lewis landed his best-remembered screen role on television, not in the movies; in 1957 he was cast as Don Alejandro Vega, the hot-headed, proud, but noble father of Don Diego Vega (Guy Williams) on Walt Disney’s excellent Zorro TV series; the show ran for two seasons and made Lewis just as familiar to the first television generation as he was to previous generations of movie-serial fans. After Zorro went off the air in 1959, he continued to appear in features and on television during the first half of the 1960s, retiring after a cameo as a Spanish UN delegate in the 1966 Batman movie.

Lewis had become a licensed Los Angeles real-estate broker back in 1940, and had very successfully followed this secondary occupation during his acting days; he continued working as a realtor for several years after the conclusion of his movie career, but by the early 1970s found himself prosperous enough to close his realty office. He enjoyed a long and happy retirement, taking up golf as an avocation and making many visits to serial and B-western fan conventions; he passed away at his home in the San Diego suburb of Rancho Santa Fe, a few days short of his ninety-first birthday.

In a 1972 interview with the serial magazine Those Enduring Matinee Idols, George J. Lewis commented that the “difficult part of working in serials was the dialogue. It was geared for a young audience and it was necessary to make it sound believable. Since the stress was mostly on action, trying to sound believable with dialogue that might be a little stilted and too explanatory for a young mind was a challenge.” An accurate statement, but Lewis modestly neglected to add that he always did an outstanding job of meeting that challenge in his assorted serial roles; whether he was making threats, issuing commands, or offering cheerful encouragement, he was always utterly believable–and always a pleasure to watch at work.

Above: George J. Lewis delays his escape from the law to listen to a few more snatches of a symphony broadcast, to the surprise of Hal Taliaferro in Federal Operator 99 (Republic, 1945).

Acknowledgements: The aforementioned magazine interview with George J. Lewis, conducted by C. M. Parkhurst and published in the October-November issue (Volume 2, Number 9) of Those Enduring Matinee Idols, provided me with this article’s Lewis quotes and with many other pieces of information. The section on Lewis in Boyd Magers’ online Serial Report digest was also very helpful, as were Everett Aaker’s book Television Western Players of the Fifties (MacFarland, 2007) and the Old Corral’s Lewis section.