January 17th, 1882 — April 1st, 1946

Above: A publicity portrait of Noah Beery Sr., circa 1943.

A major player in silent films, Noah Beery Sr. slid into B-movies in the 1930s, becoming one of the earliest and most memorable villains of the sound serial era. With his stocky build, dark complexion, moustache, and bushy eyebrows, Beery was the picture of a classic melodrama heavy, and he played his scowling, scheming villains with all the gusto of an old-time stage trouper. However, Beery’s villains had another side to them; when he was using his deep bass voice and jovial laugh to make the heroes think he was a fine fellow, he was so appealing that the audiences couldn’t blame the protagonists for being deceived. Indeed, the audiences themselves, even with knowledge of Beery’s true motives, found themselves almost liking his villainous characters; his energy and zest was infectious, whether he was smiling and joking with the hero or casually plotting the hero’s death. Fans never wanted Beery to succeed in his evildoing, but it was hard not to feel a twinge of regret whenever the magnificent old scoundrel met his inevitable fate in the final chapter.

Noah Beery was born in Kansas City, Missouri. His younger brother, of course, was the famous Wallace Beery; both boys aspired to be actors, and began to pursue a show-business career while still in their teens. Noah worked as a newsboy, circus concessionaire, lemon-drop hawker, and singer before joining a touring stage company. In 1905, he debuted on Broadway, and after spending several years there, he came to Hollywood around 1914. He quickly established himself as a leading screen heavy, playing a large number of foreign menaces–Mexicans, Arabs, Chinese–as well as Western outlaws, corrupt politicians, and gangsters. Some of his notable characterizations during this time included the thuggish but comical Sergeant Gonzales in Douglas Fairbanks’ Mark of Zorro (1920), the title role in the 1920 version of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf, and the sadistic Sergeant Lejaune in Ronald Colman’s Beau Geste (1926). When sound arrived in Hollywood, Beery’s rich, carrying voice proved well-suited to the new medium, although its decidedly American tone largely deprived him of the wide range of ethnic parts he had played in silents. However, his career began to decline in the early 1930s, for no apparent reason–possibly, the major studios simply regarded him as being too identified with the pre-talkie era. He played a few big roles in major 1930s films like George O’Brien’s Riders of the Purple Sage (Fox, 1931) and the Eddie Cantor musical comedy The Kid From Spain (MGM, 1932), but such films were now to become the exception rather than the rule for him. In 1932, producer Nat Levine, who made a regular practice of hiring once-famous silent performers, recruited Beery to appear in the actor’s first chapterplay, Mascot Pictures’ The Devil Horse.

The Devil Horse, an action-packed cliffhanger, cast Beery as Canfield, a seemingly respectable rancher who secretly led a band of outlaws in raids against his unsuspecting neighbors. Hero Bob Norton (Harry Carey), seeking to avenge his brother’s killing by the Canfield gang, joined forces with two unusual allies to battle the outlaws–Frankie Graham (Frankie Darro), a young boy whose parents had also been killed by the outlaws years ago and who had been raised by a herd of wild horses, and El Diablo, an exceptionally intelligent race horse who had escaped to join the horse herd when Canfield tried to steal him. Canfield, despite his adeptness at disguising his illegal activities, was finally exposed and defeated by his human and equine nemeses. Beery was a delight to behold in his serial debut, chortling and growling his way through his scenes and emphatically chewing away at his cigar; even his hand gestures were full of boisterousness.

Above: Noah Beery Sr. chews over a difficult question from Harry Carey in The Devil Horse (Mascot, 1932).

Above: Noah Beery Sr. and cohort J. Paul Jones react as El Diablo wins a race, confounding their plans in The Devil Horse.

Beery followed Devil Horse with a second Mascot serial, Fighting With Kit Carson, in 1933. He was cast a saloon owner named Cyrus Kraft, outwardly a good citizen but actually the leader of a ruthless gang of outlaws called the Mystery Riders. Beery spent most of the serial trying to get his hands on a gold shipment, framing scout Kit Carson (John Mack Brown) for robbery, murdering several unsuspecting victims, and even betraying his own followers in the pursuit of this goal. Carson was another exciting Mascot serial with plenty of action, and Beery was allowed even greater scope for his chicanery than in Devil Horse; in fact, the Kraft role was probably the meatiest of his entire serial career. He genially bamboozled both the heroes and his henchmen at every turn, audaciously double-crossed everyone in sight, and perpetually played with a small knife, that, when dropped, served as a signal to a hidden henchman to stab whoever was unfortunate enough to be chatting with Beery at the time. One of the early victims of the knife signal was a friendly Indian chief; interestingly, the chief’s son was played by Beery’s own son Noah Beery Jr., who was just starting out in pictures at this time but who would carve out his own impressive career in serials and features in coming years.

Above: The affable Noah Beery Sr. assures Betsy King Ross that her missing father (who Beery is secretly holding prisoner) will be all right in Fighting with Kit Carson (Mascot, 1933).

Above: Noah Beery Sr. boasts of his future wealth and power to henchman Maston Williams (back to camera) in Fighting with Kit Carson.

After appearing in many more American B films during 1933 and 1934, (including some of Paramount’s hour-long Zane Grey adaptations and a pair of Wheeler and Woolsey comedies), Beery temporarily moved to England in 1935. There, he played major supporting roles (both villainous and non-villainous) in modestly-budgeted British features, most of them mystery films such as The Crimson Circle and The Frog. He didn’t return to Hollywood films until 1937–when he appeared in his third serial, Republic Pictures’ modern-day Western Zorro Rides Again. He played a tycoon named J. A. Marsden, who was out to take over the California-Yucatan railroad by any means necessary. His ruthless plans were thwarted by James Vega (John Carroll), one of the railway’s owners and a descendant of the original Zorro. Beery had been one of the screen antagonists of the original movie Zorro, Douglas Fairbanks Sr., so his casting in this cliffhanger was quite appropriate. Unfortunately, while Zorro Rides Again was a terrific cliffhanger, Beery’s role in the serial was a very limited one; he very rarely interacted with the other characters, and spent almost all his screen time giving orders to his henchman Richard Alexander via radio. Beery handled these plotting scenes with his customary slyness, and his disgruntled reactions to his followers’ failures was enjoyable (“Zorro, Zorro, Zorro! Can’t you get rid of that man?”), but the role was nevertheless a waste of his talent.

Above: Noah Beery Sr. issues orders to his henchmen, his principal activity throughout Zorro Rides Again (Republic, 1937).

Beery’s screen credits grew extremely sparse over the next few years; it would seem he began working on stage again, as well as performing on radio, during this time. In 1940, he returned to Republic Pictures for his fourth serial, Adventures of Red Ryder. This time, his role was much meatier than in Zorro Rides Again; he played Ace Hanlon, a shady saloon proprietor who joined with villainous banker Calvin Drake (Harry Worth) to acquire a monopoly on ranch land that an incoming railroad would need for a right-of- way. When Drake and Hanlon’s henchmen murdered rancher Colonel Ryder as part of their land-grabbing campaign, Ryder’s son “Red” (Don Barry) swung into action against the badmen, eventually uncovering Drake and Hanlon as the ring-leaders. Beery played subordinate villain to Harry Worth in this outing, but actually received more screen time and higher billing than his boss, and had several opportunities to exhibit his unique brand of bluff, cigar-chomping villainy. His hearty approach to villainy contrasted well with Worth’s dry and sardonic manner, and the two made a fine team of evildoers in what would prove one of Republic’s best serials.

Above: Ray Teal (left) and Noah Beery Sr. tie up crooked sheriff Carleton Young so that Teal’s “escape” from Young’s jail won’t look like an inside job in Adventures of Red Ryder (Republic, 1940).

Above: Don Barry (far right) has the drop on Bob Kortman (with eyepatch), Art Dillard, and Noah Beery Sr. in Adventures of Red Ryder.

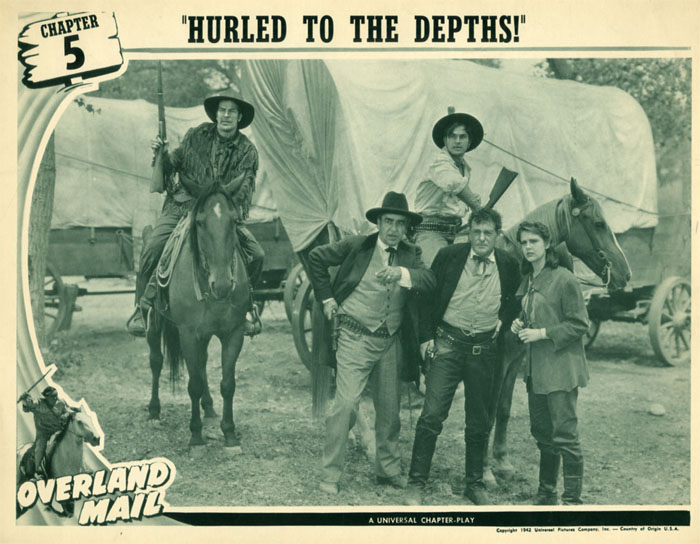

Beery struck up a friendship with Don Barry, the star of Red Ryder, becoming something of a mentor to the young actor; Republic, probably at Barry’s request, featured Beery in several of Barry’s B-western vehicles over the next three years (among them The Tulsa Kid and Outlaws of Pine Ridge). For a change, he played fatherly and sympathetic figures in all of these films; the few remaining years of his career would see him continuing this move to good guy roles, with one notable exception. The exception was Overland Mail (Universal, 1942), Beery’s final serial, which once again featured him in his specialty role, that of a congenial but double-dealing frontier businessman. This time, Beery’s character Frank Chadwick was using renegades and Indians to drive Tom Gilbert’s (Tom Chatterton) stage line out of business so he could snap up Gilbert’s government mail contract; his opponent was government investigator Jim Lane (Lon Chaney Jr.), who was aided by Sierra Pete (Noah Beery Jr., again appearing with his father). Chadwick was a quintessential Beery villain–crafty and ruthless, but humorous and almost likable at the same time. When the defeated Chadwick surprisingly died repentant in the last chapter, bequeathing his wealth to Gilbert as an atonement, the gesture didn’t seem at all unbelievable, thanks to the measure of complexity Beery’s acting had imparted to the character.

Above: Lon Chaney Jr. has the drop on henchman Harry Cording, while an apparently amused Noah Beery Sr. prepares to deny all knowledge of his cohort’s existence in Overland Mail (Universal, 1942).

Above: Noah Beery Sr. points towards oncoming Indians; Tom Chatterton and Helen Parrish are next to Beery, while Don Terry is mounted at left and Noah Beery Jr. sits his horse behind his father in Overland Mail.

Most of Beery’s remaining career was spent at low-budget Monogram Pictures, where he appeared in several “East Side Kids” films with Leo Gorcey and Huntz Hall (Clancy Street Boys, Mr. Muggs Steps Out, and similar titles). However, he did manage three decent-sized roles in major MGM movies–the Western drama Gentle Annie, and two of his brother Wallace’s starring vehicles–Barbary Coast Gent and This Man’s Navy. Navy was released in 1945; the following year, Noah was set to appear with Wallace again in a radio play called “Barnacle Bill,” but he died of a heart attack a few hours before the broadcast.

While Wallace Beery built his fame playing lovable rogues, and Noah Beery Jr. almost always played amiable if rascally sidekicks, Noah Beery Sr.’s characters were usually unsympathetic and purely villainous. And yet, the Beery charm, apparently a family trait, managed to show itself in many of Noah Sr.’s most despicable heavy characterizations–particularly in his serials, where he kept audiences continually oscillating between disapproval of his evil deeds and admiration for his resource, ingenuity, and sheer audacity. There are few serial villains that audiences “loved to hate” as much as Noah Beery Sr.; his cliffhanger bad guys were simply the dirtiest, sneakiest, most hypocritical, and most charismatic heavies in the West.

Above: A portrait of Noah Beery Sr. from the 1940 Republic B-western Pioneers of the West.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Jim Beaver, author of the Internet Movie Database’s min-biography of Beery, for information on Beery’s early years and his death.

Thank you very much for this highly informative article/biography on Noah Beery, Sr. I’ve always enjoyed watching Wallace Beery and nephew Noah Jr. It helps draw a more complete picture of all their careers by learning of all that Noah Sr. did and was doing. “My compliments to the chef!” , as they say.

Noah Sr. may have chewed the scenery as a villain, but I don’t think anyone did the quick-excuse-and-a-hearty-laugh-when-he-gets-caught-in-a-lie routine better than he did. Other villains would just tough it out, but Noah Sr. always tries to smooth it over.

He is the top most horrible villian, but he is lovable. He comes across as a rotten person. But he’s the best villan, besides harry woods, dick curtis and glen strange and roy barcroft. But noah berry senor was the greatest. I’ve been looking for informotion on him for a while. So thank you for giving me information.

sincerly, Sherry Hunt