November 15th, 1900 — February 20th, 1969

Above: Jack Ingram in a publicity still from the serial Zorro Rides Again (Republic, 1937).

Jack Ingram’s career as a B-western and serial heavy ran from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s, and during that lengthy period he probably played the lead henchman (or “action heavy”) more often than any of his contemporaries did. Tough in appearance, lazy in manner, and drawlingly slow of speech, Ingram typically played crafty, gruff, and insolent heavies, characters who would react to opposition (from the heroes) or rebuke (from the principal villains) with sarcastic irritation. His performances were always enjoyable, and were a particular asset to Columbia Pictures’ under-energized post-war serials, in which he was a consistent presence.

Ingram was born John Samuel Ingram in Chicago, but apparently spent at least part of his youth in Texas; at any rate, he was living there when he enlisted in the 8th Field Artillery in 1917, after representing himself as eighteen years old (instead of his actual age of fifteen). In 1918 he shipped out to France for the tail end of World War 1; he returned to America after his 1919 discharge in 1919. For a time, he studied law at the University of Texas, but at some point during the 1920s abandoned a legal career for an acting one–traveling the country first as a minstrel-show performer, and then working in several stage-acting companies, among them Mae West’s. He didn’t make it to Hollywood until 1935, when he played a minor good-guy role in the new-born studio Republic Pictures’ 1935 John Wayne B-western, Westward Ho.

Ingram would continue to work principally at Republic for the rest of the 1930s; 1936 saw him playing bit parts in Republic’s Gene Autry and John Wayne B-westerns (The Singing Vagabond, Winds of the Wasteland, and others), as well as two Republic serials, Undersea Kingdom and The Vigilantes Are Coming. His roles in these cliffhangers were miniscule—an appearance as one of Atlantean tyrant Unga Khan’s guards in Kingdom, and bits as both a badman and a vigilante in separate chapters of Vigilantes.

In 1937, Ingram continued to play plenty of bit parts at Republic and other studios, but also started taking larger roles, most notably sidekick parts in Conn Productions’ Kermit Maynard B-westerns Valley of Terror and Whistling Bullets. During this time, he appeared (very briefly) in his first Columbia serial, playing an undercover police detective who helped a colleague by starting a brawl in one chapter of Jungle Menace. Over at Republic, he took bits in more B-westerns and in the serials Dick Tracy (as a reporter) and SOS Coast Guard (as a crooked sailor) before the studio gave him his first credited cliffhanger role in Zorro Rides Again. Though largely a background henchman (Carter by name), subordinate to both Richard Alexander and Bob Kortman, Ingram appeared throughout the serial, had his share of dialogue, and tangled frequently with the hero. He played his character as a straightforwardly thuggish type, minus the lazy sarcasm he would develop as his career progressed.

Above: Jack Ingram, Bob Kortman, and Richard Alexander (left to right) threaten Helen Christian and Reed Howes in Zorro Rides Again (Republic, 1937).

1938 found Ingram slipping permanently into the henchman groove he would occupy for the rest of his time in Hollywood, playing both minor and major heavies in B-westerns for Republic, Conn Productions, and others. Also in 1938, he played another background henchman (unnamed) throughout Republic’s popular chapterplay The Lone Ranger, and did a walk-on as a non-villainous radio operator in another Republic cliffhanger, The Fighting Devil Dogs. A third 1938 Republic serial, however, gave him his first meaty turn in a chapterplay: Dick Tracy Returns featured him as Slasher, one of the five sons of gangster patriarch Pa Stark (Charles Middleton). Ingram, though billed at the bottom of the credits, had a larger role than any of the actors playing his siblings (John Merton, as the eldest and toughest Stark, survived longer but had less dialogue than Ingram). Ingram gave the knife-wielding Slasher a keenly aggressive and irritable manner that fit his nickname, and came off as his father’s right-hand man where plotting was concerned. Tracy marked the debut of Ingram’s enduring serial persona, allowing him to snap off typically callous lines like “that’s their tough luck” (in reference to an unexpected class of students scheduled to be blown up in a targeted observatory).

Above: John Merton, Jack Ingram, and Raphael Bennett in Dick Tracy Returns (Republic, 1938).

Ingram continued to appear in B-westerns for Republic, but also branched out to the Bs of Monogram, Columbia, and others studios during 1939. By 1940 he was firmly established as a leading cowboy heavy, although he occasionally was allowed to play sympathetic roles in a few of his Western features. 1940 also saw the beginning of Ingram’s long association with Columbia’s serials; their 1940 chapterplay The Shadow featured him as Flint, the leading henchman of a criminal called the Black Tiger and a foe to crimefighter Lamont Cranston (Victor Jory). The Shadow was the first of several serials directed by James W. Horne, unique among their peers thanks to their director’s penchant for playing them for comedy; Ingram’s gruff and snappish manner made him a perfect foil for the type of buffoonery typical to Horne serials, and Ingram would become a recurring member of the director’s serial stock company. However, in The Shadow Ingram played his role fairly straight (aside from exaggerated scowls when confronting the good guys); though snappishly terse towards his underlings and slightly nervous in the presence of his boss, he didn’t play either his terseness or nervousness for laughs, as he would in several subsequent Horne serials.

Above: Jack Ingram face to face with Victory Jory as The Shadow (Columbia, 1940).

Terry and the Pirates (Columbia, 1940), another Horne chapterplay, again cast Ingram as the leading henchman and didn’t involve him in much comedy; he played his character (Stanton) as cagey and tough, and seemed to largely ignore the goofy antics of the other cast members. Ingram became a full participant in such antics with his next serial, Horne’s The Green Archer (also Columbia, 1940). As Brad, one of the chief accessories to outrageously cranky jewel thief James Craven, one of his principal duties was to dress up as the ghostly “Green Archer” and eliminate Craven’s enemies. His other principal duty, however, was to be mistaken for the villains’ mysterious opponent (a heroic version of the aforesaid Green Archer) and pummeled by his fellow henchmen, particularly Kit Guard as “Dinky.” Ingram’ skill for conveying exasperation made the repeated Brad-Dinky encounters very amusing; his irritation with his colleague increased to hilarious levels as the serial progressed.

Above: Jack Ingram triggers a microphone inside an ancient idol in order to fool some gullible natives in Terry and the Pirates (Columbia, 1940).

Above: Jack Ingram bickers with Kit Guard, to the irritation of the seated James Craven in The Green Archer (Columbia, 1940). Victor Jory is choking Constantine Romanoff on the border of this lobby card.

Deadwood Dick, the most straightforward and least comic of Horne’s chapterplays, gave Ingram yet another lead henchman role, but he played his part rather more comically than the rest of the cast. As Buzz Ricketts, lieutenant of a masked outlaw called the Skull, Ingram acted more harried and jittery than menacing, particularly when being bawled out by his boss or confronted by the forceful Don Douglas as Deadwood Dick. In White Eagle (Columbia, 1941), Ingram played chief henchman to outlaw boss James Craven, but was much more gruff and self-possessed than in Dick. Indeed, he came off as more capable than his boss; Craven, as in Green Archer, ranted and raved hysterically whenever things went wrong, and it frequently fell to Ingram’s character to calm him down.

Above: Jack Ingram and another henchman utilize a frontier speaking tube in Deadwood Dick (Columbia, 1940).

Above: Jack Ingram talks a furious James Craven out of killing henchman Bud Osborne, in this scene from White Eagle (Columbia, 1941).

The 1940s found Ingram continuing his career as a prolific B-western badman for all the principal producers of cowboy movies. On the serial front, he took a break from Columbia and Horne to appear in Republic’s 1941 chapterplay King of the Texas Rangers, one of the studio’s best releases. Ingram was Shorty, one of a group of modern-day outlaws working for a Nazi spy ring in the Texas oil fields. He shared henchman duties with a formidable group that included Roy Barcroft, Kenne Duncan, and Bud Geary, and was not spotlighted as he had been in his Columbia releases–but still had his share of good villainous moments.

Above: Jack Ingram (center) and Robert Barron surprise a dam guard (Eddie Dew) in King of the Texas Rangers (Republic, 1941).

Ingram returned to Columbia for Horne’s final serial, Perils of the Royal Mounted (1942), playing a French-Canadian thug named Baptiste, one of outlaw boss Kenneth MacDonald’s main followers. Once again, Ingram played the part for laughs, being alternately exasperated and flustered, although he didn’t try to put a French accent on over his Midwestern drawl—which could hardly have made the serial sillier than it already was.

Above: Jack Ingram and George Chesebro are cornered by Indians in Perils of the Royal Mounted (Columbia, 1942).

Valley of Vanishing Men (Columbia, 1942), paired Ingram with MacDonald again; Ingram was in more typical form as a crafty outlaw named Butler, but his role was much smaller than in Perils of the Royal Mounted; despite his high billing in the serial’s credits, he was strictly a background member of the henchman pack in Vanishing Men. He was also a pack member in Batman (Columbia, 1943), a thug named Klein who worked for Japanese spy J. Carroll Naish; as in Vanishing Men, he had a few noticeable bits and appeared throughout of the serial, but stayed largely in the background.

Above, from left to right: George J. Lewis, Jack Ingram, Dick Curtis, and Tom London discuss the unconscious Batman (Lewis Wilson) in the 1943 Columbia serial of the same name.

Ingram had appeared in plenty of Universal Pictures’ B-westerns in the 1930s and early 1940s, but he didn’t make a Universal serial until 1944, when he appeared in The Great Alaskan Mystery and Raiders of Ghost City. Alaskan Mystery gave him a single-chapter bit as a Nazi agent named Kruger who attempted a one-man plane hijacking and engaged in a fight with hero Milburn Stone; Ingram wore a mask during this sequence but was immediately recognizable by his voice. His role in Raiders was much meatier; he was perfectly cast as Braddock, a greedy, cynical, and vicious guerilla under the command of noble Confederate officer Regis Toomey. Ingram was suitably surly when Toomey was rebuking him for unmilitary excesses, properly nasty when battling hero Dennis Moore, and appropriately shrewd when plotting with villain Lionel Atwill to betray Toomey and seize Confederacy-bound gold. Ingram sandwiched one Columbia serial appearance between these two Universal chapterplays, a one-scene bit as a town crier in The Desert Hawk.

Above: Jack Ingram gets slugged by Dennis Moore in Raiders of Ghost City (Universal, 1944).

Manhunt of Mystery Island (Republic, 1945), featured Ingram as an unusually respectable character, a businessman named Edward Armstrong who was one of four co-owners of the titular Pacific island. Armstrong and his partners were all descendants of a pirate named Captain Mephisto; one of the quartet had discovered how to transform himself into a double of his ancestor (Roy Barcroft) and was using the dual identity to engage in criminal activities. Though he began the serial quite affably, Ingram’s character became more irritable and suspicious as matters progressed, and by Chapter Ten emerged as the leading suspect for Mephisto’s alter ego; he proved to be innocent, however, and was gunned down by the villains in Chapter Eleven after a noble attempt to help hero Richard Bailey discover Mephisto’s real identity.

Above: Jack Ingram in Manhunt of Mystery Island (Republic, 1945).

In 1945, Ingram again took on a major henchman role in a Columbia cliffhanger, Brenda Starr, Reporter. The first of a long line of serials made for Columbia by the cheapskate producer Sam Katzman, Brenda was a rather dull affair with a weak storyline and virtually no action, but Ingram acquitted himself well as a tough gangster named Kruger, the chief lieutenant of gangster Frank Smith (George Meeker) and a mysterious “big boss”–coldly gunning several people down with a self-satisfied sneer, and snapping back aggressively at Smith when the latter rebuked him or tried to intimidate him by talking about the unseen boss.

Above: Anthony Warde holds a gun on Horace B. Carpenter as Jack Ingram prepares to blow up a mine shaft in Brenda Starr, Reporter (Columbia, 1945).

Ingram also played a principal henchman in Rudy Flothow’s final Columbia serial production, released shortly after Brenda Starr. The Monster and the Ape was a very uneven chapterplay; like Brenda, it was slow-paced and poorly-plotted, albeit with a higher action quotient. It also featured some unexpected comedy from Ray Corrigan as the titular ape, a trained killer gorilla called Thor that chief villain George Macready used to knock off rival scientists. Ingram, as Dick Nordik, was a crooked zookeeper whose job was to transport Thor to and from the scene of his crimes, and who continually registered irritation at the easily-distracted simian’s antics en route. Despite the headaches the ape caused him (he spent most of his time yelling “Thor! Stop that!”), Ingram’s character seemed to have a liking for his murderous pet, and was comically crestfallen when Macready proposed to abandon the gorilla. Ingram’s harried and rather bumbling character–essentially a comic foil for his scene-stealing simian friend–was overall something of a throwback to the henchmen he had played in Horne’s serials.

Above: Stanley Price, Willie Best (seated), and Jack Ingram in The Monster and the Ape (Columbia, 1945).

Federal Operator 99 (Republic, 1945), was, with one exception, Ingram’s last Republic serial; he appeared in the first chapter as a thug named Riggs who was gunned down by the hero (Marten Lamont) after a brief altercation. Later in 1945, he took another major Columbia serial role in Jungle Raiders, playing—surprisingly enough—a bona fide good guy, a seasoned explorer named Tom Hammil. Ingram dropped his customary sneer and made his character seem cool-headed, good-natured, and dependable; though secondary to star Kane Richmond, he took the lead among the protagonists when Richmond’s character was absent and came off as a strong supporting hero.

Above: John Elliott (far left) and Jack Ingram discuss their expedition with trading-post proprietor Charles King in Jungle Raiders (Columbia, 1945).

Who’s Guilty, Ingram’s final 1945 Columbia chapterplay, gave him another good guy role as Sergeant Smith, a somewhat perplexed but helpful policeman who assisted state detective Robert Kent in investigating a series of murders centering around a wealthy family’s mansion. He was back to nastiness in The Scarlet Horseman (Universal, 1946), as an outlaw named Tragg who served an opportunistic badman called Zero Quick (Edward Howard). Horseman had too many villainous characters, and Ingram’s Tragg frequently got lost in the complicated struggles between Quick, Virginia Christine’s Carla Marquette, and Victoria Horne’s ambitious Loma; he spent most of his time in the background before finally getting gunned down by star Paul Guilfoyle. He did get one memorably typical Ingram moment, though, when he snarled at Shakespeare-quoting henchman Guy Wilkerson and revealed his character’s complacent ignorance of literature.

Above: Robert Kent and Jack Ingram overpower Davison Clark in Who’s Guilty (Columbia, 1945).

Above, from left to right: Jack Ingram, Edward Howard, Edmund Cobb, and Guy Teague in The Scarlet Horseman (Universal, 1946).

Hop Harrigan (Columbia, 1946), another of Columbia’s weaker chapterplays, allowed Ingram to play a shrewd police detective named Riley–who didn’t enter the serial until Chapter Nine, but still managed to unmask a treacherous secretary and the serial’s mystery villain (the “Chief Pilot”) almost unaided, working from a single clue (a would-be assassin’s hat). Ingram’s long-winded explanation of how he arrived at his conclusions wasn’t really necessary to the plot (like many other scenes in Harrigan, it was obviously intended as narrative padding)–but it was entertaining to watch Ingram complacently and assuredly issue uncharacteristically Sherlockian pronouncements.

Above: Jack Ingram, on the right side of the law for a change, arrests evildoer Peter Michael in Hop Harrigan (Columbia, 1946).

Ingram was back to playing a heavy in his next Columbia serial, the lackluster Chick Carter, Detective (also 1946); as Mack, the cagy but basically loyal right-hand man of crooked nightclub owner Charles King, he was less selfish and less violent than in many of his Columbia henchman roles–spending most of his time either helping King engineer an insurance fraud or (later) dodging the police after becoming a murder suspect. He even came off as likable in a couple of scenes, when crankily but fearlessly standing up to the real murderer, the ruthless gangster Vasky (Leonard Penn)–who eventually bumped him off in Chapter Eleven.

Above: “OK, wise guy, I’ll know you the next time I see ya.” Jack Ingram vows vengeance on an off-camera Leonard Penn in Chick Carter Detective (Columbia, 1946), after narrowly escaping Penn’s gunfire.

Ingram was more thoroughly mean in The Mysterious Mr. M. (1946), his last non-Columbia serial of note and Universal’s final cliffhanger outing. As a prominent henchman named Bill Shrag, he carried out the orders of the titular mystery criminal with his customary tough craftiness–but as, in Scarlet Horseman, was somewhat pushed into the background by an unusually large group of higher-ranking villains (played by Edmund MacDonald, Danny Morton, and Jane Randolph). He still had some good scenes, however–particularly when he unconcernedly sneered at the good guys after being arrested, and when he eagerly tried to scrape acquaintance with his mysterious boss only to be coldly rebuffed.

Above: Danny Morton and Jack Ingram in pursuit of a victim in The Mysterious Mr. M (Universal, 1946).

For the rest of the 1940s, Ingram would spend most of his time working in B-westerns for Monogram and Columbia, and serials for Sam Katzman’s Columbia chapterplay unit. 1947 found him playing action heavy in the Katzman serials Jack Armstrong, The Vigilante, and The Sea Hound. Armstrong, the weakest of the three, still allowed Ingram some good sardonic moments as Blair, the chief henchman of would-be world ruler Charles Middleton. The Vigilante, one of Katzman’s better serials, featured Ingram as Silver, who managed villain Lyle Talbot’s nightclub and also delivered Talbot’s orders to his henchmen. Ingram’s Vigilante character was slicker and less grumpy than the usual Ingram henchman, and participated in little active villainy; he was, however, quite treacherous–eventually attempting to chisel his boss out of some priceless red pearls and getting gunned down as a result. The Sea Hound, an atmospheric tropical-island adventure, was somewhere between Armstrong and Vigilante in quality; Ingram was characteristically gruff and sarcastic here as Murdock, the henchman of island criminal Robert Barron; his harshness played well off of Barron’s sleekness.

Above: Jack Ingram and Lyle Talbot bend over the corpse of Edmund Cobb in The Vigilante (Columbia, 1947).

Above: Jack Ingram, disguised as a Malay, sneaks aboard ship in The Sea Hound (Columbia, 1947).

With a few exceptions, Ingram would now play the same character in all of his remaining Columbia serials: the grumpy, sly, and sometimes untrustworthy henchman of a smoother boss. Brick Bradford (1948), featured him as Albers, the right-hand man of slick scientific villain Charles Quigley; here, his character remained loyal to his boss, even when forced (during an oddly odd comic sequence) to pump up flat tires while said boss impatiently snapped at him. Tex Granger (also 1948) cast Ingram in a more duplicitous henchman role as Reno, a tough outlaw leader who joined with rogue sheriff Smith Ballew to undermine and eventually overthrow town boss I. Stanford Jolley, only to be later gunned down by the ungrateful Ballew. Both Bradford and Granger were highly uneven, but Ingram was his usual solid self in both outings.

Above, left to right: Jack Ingram, Charles Quigley, and Fred Graham in Brick Bradford (Columbia, 1948).

Above: Jack Ingram, Smith Ballew (far right) and their cohorts examine an express company box in Tex Granger (Columbia, 1948).

Superman (also 1948), one of Columbia’s better Katzman-produced outings, gave Ingram another henchman role as the sneering, wisecracking Anton–a subordinate to both the Spider Lady (Carol Forman) and her lieutenant (George Meeker), but the man who orchestrated most of the villains’ field activities. Captured by Superman (Kirk Alyn) in Chapter Thirteen, Ingram was blasted with a death ray by Forman in Chapter Fourteen to prevent him from talking.

Above: Jack Ingram, Noel Neill, and Terry Frost in Superman (Columbia, 1948).

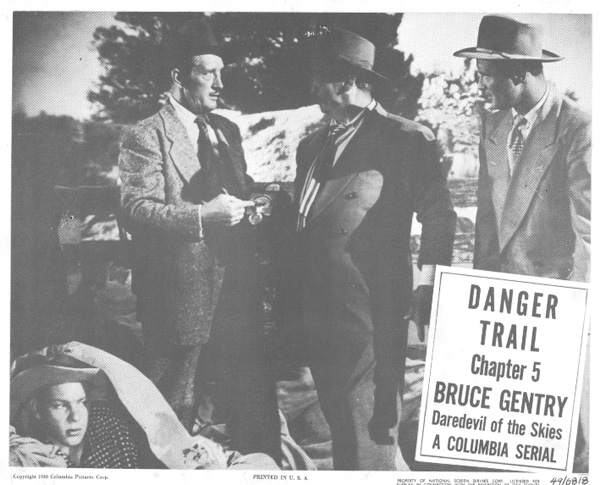

Congo Bill, yet another 1948 Columbia release, gave Ingram a break from villainy and cast him as Cameron, an enigmatic but helpful jungle adventurer who assisted hero Congo Bill throughout the serial and eventually proved to be an undercover colonial official out to break up the villains’ gold-smuggling schemes. Ingram came off as both likable and smoothly cagy in this part, balancing laid-back affability with cool imperturbability. Bruce Gentry (Columbia, 1949), featured Ingram in more familiar mold as Allen, the chief agent of a spy ring headed by Tristram Coffin and a mystery villain called the Recorder. Ingram by now could have played such roles in his sleep, but he gave his part plenty of cranky energy nonetheless, bouncing sarcastic dialogue off his underlings with flair.

Above, from left to right: Jack Ingram, Nelson Leigh, Don McGuire, and Neyle Morrow in Congo Bill (Columbia, 1948).

Above: Jack Ingram plots with Charles King (center) and another henchman in Bruce Gentry (Columbia, 1949)., while Ralph Hodges eavesdrops

In 1944, Ingram had purchased a tract of prairie land and begun to develop it into a movie location ranch that he rented to various studios. The revenue from this property he invested wisely, and by 1950 he was financially well-off enough to slack off his film work a bit and tour with his own Western musical stage show. He continued working in B-westerns and serials during the early 1950s, however, albeit not as frequently as during the 1940s. Cody of the Pony Express (Columbia, 1950) featured him as an outlaw named Pecos, George J. Lewis’ lead henchman until he was killed halfway through, as punishment for threatening to talk after being captured. Atom Man Vs. Superman (Columbia, 1950) cast him as Luthor’s (Lyle Talbot) secondary henchman Foster, a role pretty similar to his Anton in the previous Superman serial—although this time he avoided being killed off by his boss.

Above: The seated Jack Ingram asks some dangerous questions of boss George J. Lewis (wearing suit).

Above: Jack Ingram looks complacent as Rusty Wescoatt questions Noel Neill in Atom Man vs. Superman (Columbia, 1950).

Don Daredevil Rides Again, (Republic, 1951), gave Ingram a small recurring role as a shifty bartender named Jack who periodically spied on the heroes and relayed their plans to the villains. Roar of the Iron Horse (Columbia, 1951) featured Ingram as a seeming good guy, a railroad contractor named Homer Lathrop. Unsurprisingly, though, he was eventually revealed as the secret leader of the outlaws plaguing the railway. Ingram did well in his only chapterplay “brains heavy” part, playing Lathrop with enough shifty smugness to make his villainy obvious to the audience but maintaining enough of a good-natured façade to make his deception of the leads (Jock Mahoney, Hal Landon, and Virginia Herrick) plausible.

Above: Jack Ingram and Rusty Wescoatt in Roar of the Iron Horse (Columbia, 1951).

Captain Video (Columbia, 1951) cast Ingram as Aker, the minion of treacherous scientist Dr. Tobor (George Eldredge). Eldredge’s Tobor was in turn the subordinate of the outer-space dictator Vultura, played by Gene Roth; Roth and Eldredge received the lion’s share of the serial’s villainous moments, and Ingram didn’t get enough screen time to really qualify as a full-fledged action heavy–only appearing in about half the serial’s chapters, and receiving very little dialogue overall.

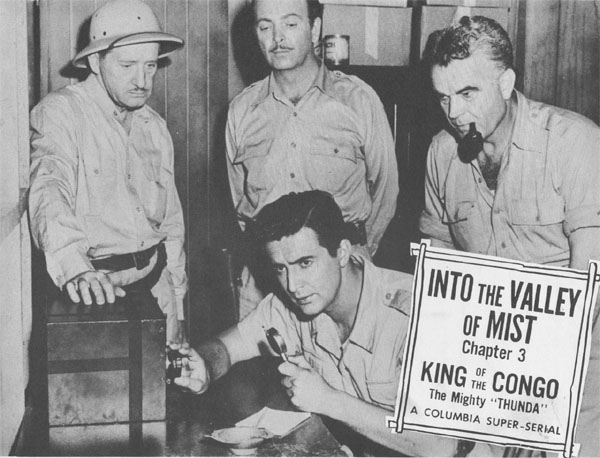

King of the Congo (Columbia, 1952), like Ingram’s two preceding jungle serials, gave him a sympathetic role. As in Congo Bill, he was a good-guy colonial agent operating in Africa; his character this time was Clark, an ostensible member of a Communist spy ring who provided covert aid to jungle hero Thunda (Buster Crabbe) while maintaining an undercover pose as a henchman. Ingram’s sly and laconic demeanor was well-suited to this double-agent role. By now, B-westerns had virtually perished as a film genre, and serials had only three years of existence left; Ingram now found himself working chiefly in television (playing heavies in series like The Cisco Kid and Adventures of Kit Carson) and A-features (usually taking bit roles).

Above, standing left to right: Jack Ingram, Leonard Penn, and Bart Davidson in King of the Congo (Columbia, 1952). Rick Vallin is seated at the radio.

Ingram made one more serial in 1954, Columbia’s Riding with Buffalo Bill. A very low-budgeted outing starring Marshall Reed and built largely around mammoth amounts of stock footage from Deadwood Dick, Valley of Vanishing Men, and other Columbia Western serials, Bill cast Ingram as a grumpy outlaw named Ace, who commanded the followers of would-be land baron Michael Fox. Dressed in the costume he had worn in Deadwood Dick, Ingram went through his henchman paces one more time, and frequently served as a bridge between the new and old footage, appearing prominently in both. The chapterplay was an interesting commentary on the longevity of Ingram’s serial career; the heroes opposing him and the villains bossing him had been replaced by others over the past decade, but he was still filling the same function he had back in the early 1940s.

Above, from left to right: Gregg Barton, Jack Ingram, and Michael Fox in Riding With Buffalo Bill (Columbia, 1954).

Ingram, by now financially independent, bought his own yacht in 1955 and sold his movie ranch in 1956; these actions signaled his virtual retirement from the picture business. He would occasionally pop up in late 1950s films and TV shows, but only on a very infrequent basis; one of his last theatrical assignments was an uncredited part in the 1957 A-western Utah Blaine, produced by his old employer Sam Katzman. His film career had ceased entirely by 1960; he passed away in Canoga Park, California nine years later.

Although a large percentage of his cliffhanger outings were either tongue-in-cheek (his Horne serials) or slow-paced and under-budgeted (many of his Katzman serials), Jack Ingram remains perhaps the best-remembered of all serial henchmen. Uneven as his vehicles were, their sheer number established him as the longest-lasting and most prolific action heavy of the sound serial era. More importantly, the consistency of his own performances, in spite of production handicaps, found a firm place for him in serial fans’ esteem. Ingram is not remembered as much for one particular role as he is for his composite screen personality; whether his name was Foster, Murdock, Anton, or Reno, his harsh, grouchy, and sarcastic characterizations were always a memorable counterweight to the seriousness of heroes and the smooth unctuousness of brains heavies.

Above: Jack Ingram, up to no good in a lobby card for Bruce Gentry (Columbia, 1949).

Acknowledgements: I am indebted to the Old Corral’s detailed and interesting page on Jack Ingram for the biographical information in this article.