Republic, 15 Chapters, 1937. Starring Ralph Byrd, Carleton Young, Fred Hamilton, Kay Hughes, Smiley Burnette, John Picorri, Lee Van Atta, Francis X. Bushman, and ? as The Lame One.

Dick Tracy chronicles the efforts of ace G-man Dick Tracy (Ralph Byrd, playing the role for the first of seven times) to destroy the Spider Ring, a ruthless and resourceful criminal syndicate headed by a mysterious mastermind known as the Lame One. The syndicate’s activities range from fur thievery to espionage to gold robbery to claim-jumping, and Tracy has his hands full combating their crimes. Tracy also has a personal stake in his battle with the Spider Ring: his attorney brother Gordon (Carleton Young) has been kidnapped by the Lame One’s agents. Unknown to Dick, Gordon has undergone brain surgery by the Lame One’s deranged accomplice Moloch (John Picorri), and, his personality altered, is now the right-hand man of the Lame One and the field commander of the Spider Ring. As Moloch himself puts it, “Brother against brother–one good, one evil–I wonder which will win?”

Dick Tracy, the first of Republic’s quartet of Tracy chapterplays and also Republic’s first serial adaptation of a comic strip, has always garnered more respect for its historical importance than for any qualities of its own. Critics from Alan G. Barbour to Leonard Maltin have dismissed Dick Tracy as the weakest of the four Tracy serials, and fan-critics tend to follow their lead. While Dick Tracy lacks the slickness of Republic’s subsequent Tracy outings, this critical consensus is still more than a bit unfair; Dick Tracy is practically as swift-paced as its successors, while, in the areas of characterization and spooky atmosphere, it’s often superior to the later three Tracy outings.

The fact that this first Tracy outing is directed by Alan James and Ray Taylor–instead of William Witney and John English, who would helm the three later entries in the series–undoubtedly has something to do with its poor reputation. However, while Dick Tracy lacks the smooth, acrobatic fistfights that Witney and English would bring to their serials, it’s still fast-paced and never dull for an instant, thanks in large part to a script that moves swiftly between a variety of locations, and to the experienced direction of James and Taylor–neither of whom were the innovators Witney was, but both of whom knew how to keep things moving. The plot takes our heroes to the waterfront, to the desert, to abandoned factories, to old manor houses, and into the sky (via airplanes and zeppelins). Most of these locations really are locations, by the way, not just studio sets–Dick Tracy, like the Mascot serials that preceded it and several of the 1930s Republic serials that followed it, benefits greatly from lots of outdoor shooting in and around real factories, ships, office buildings, and so forth. These real-life locations provide excellent backdrops for some excellent chase; the lengthy Chapter Two pursuit at the abandoned “energy plant” is particularly outstanding.

Above: Shots from the terrific Chapter Two chase sequence.

While the fights in this serial aren’t up to the standard of Republic’s later serial brawls, but they’re as good as most brawls in Mascot’s serials and in contemporary Universal serials. One of the best fistfight sequences takes place in a waterfront cafe in Chapter Six, with Fred Hamilton and Smiley Burnette taking on a gang of Spider henchmen in the main room while Ralph Byrd chases another thug down a flight of stairs, fighting off intervening crooks all the way down. The fistfight in Chapter Eight, with Byrd taking on a whole roomful of Spider henchmen, is also energetic and exciting, as is the abovementioned extended fight/chase through the abandoned plant in Chapter Two (which includes some brilliant acrobatics by Byrd’s stunt double George DeNormand) and the shorter chase across the rooftop of the Lame One’s mansion in Chapter Five. There are also innumerable car chases, airplane chases, and motorboat chases scattered throughout the serial, all executed with skill and enhanced by excellent miniature work.

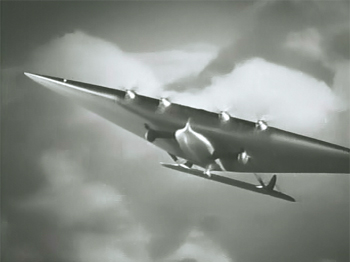

Those miniatures–courtesy of special effects wizards Howard and Theodore Lydecker–are another outstanding attribute of Dick Tracy, even more striking than the location shooting. The most impressive bit of work is in the first chapter, which features the awe-inspiring spectacle of the Spider Ring’s “flying wing” attacking the Bay Bridge with its “sonic disintegrator” device. Both the bridge miniature and the wing model are very convincing, and the site of the wing eerily cruising above the endangered bridge is not one that is easily forgotten. The Lydeckers also contribute several other vivid moments, including a highly impressive dirigible crash in Chapter Nine, and a memorable airplane/bridge collision in Chapter Two.

Above: The magic of the Lydeckers at work. First, the Flying Wing soars above the targeted Bay Bridge (top left), as a group of trucks are trapped in a bridge traffic-jam caused by a Spider Ring agent (top right); then, the Wing zooms in closer (bottom left) to start shaking the structure down (bottom right) with sonic rays.

Several of the serial’s cliffhangers center around the aforementioned miniatures, while others are less large-scaled but handled with equal effectiveness–including the Chapter Six ending, with Tracy being dragged underwater by a submarine, and the near-horrific Chapter Fourteen ending, which has Tracy on the verge of undergoing one of Moloch’s brain operations. There are some “cheater” cliffhangers, in which we see a resolution that differs from last week’s peril (the cheat in the resolution to Chapter Seven, for example) but none as blatant as those in Republic’s two preceding serials, The Vigilantes Are Coming and Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island; happily, the studio would almost completely work this trait out of its serial system by the next year.

As already mentioned, Tracy’s script (by George Morgan, Morgan Cox, Barry Shipman, and Winston Miller) does an admirable job in keeping the plot on the go, sending Tracy from one Spider crime scene to another without sacrificing coherence. There are a few contradictions in the script, such as the villains’ reference to a character’s “bearing the mark of the Spider,” when said character in question was never marked, or the criminal Gordon Tracy’s angry reference to “my G-man brother” when Moloch is supposed to have wiped Gordon’s memory of his past life clean, but there are no major plot holes to be found. The mystery villain angle of the serial, as several reviewers have commented, is somewhat undernourished; there are only two suspects who make easily forgettable token appearances throughout the serial, but it’s not as amateurishly handled as some writers have claimed–it is easy enough to recognize the guilty suspect, when he’s finally unmasked.

The writers also do a nice job in making both the serial’s heroes and its villains memorable and interesting, and they’re assisted by a stellar cast. Ralph Byrd throws himself wholeheartedly into his role, conveying determination and almost frantic energy, but also imparting Tracy with considerable geniality. Byrd seems genuinely congenial when chatting with Tracy’s circle of friends, genuinely aggressive when confronting the villains, and–very rare in a serial hero–genuinely worried when facing what seems to be certain death. Byrd succeeds in making his sleuth seem recognizably human, despite Tracy’s almost Sherlockian detective skills and near-superhuman fighting prowess, which is probably the reason he played the role not only in three later serials, but in two movies and a TV show as well.

Above: Ralph Byrd’s Tracy, flanked by his trusty aides Gwen (Kay Hughes) and Steve (Fred Hamilton).

Tracy’s friends each emerge as interesting and likable in their own right, interacting very nicely with Byrd and with each other. Fred Hamilton, as Tracy’s trusty second-in-command Steve Lockwood, is excellent; perfectly competent, but flippant and casual even in the tightest circumstances (unusually for a supporting hero, he even smokes cigarettes more than once); his easygoing demeanor provides a nice contrast to Byrd’s seriousness. Kay Hughes, one of the prettiest but least-known serial heroines (she reminds me somewhat of Maureen O’Sullivan), lends a lot of charm to her role as Gwen Andrews, Tracy’s very capable laboratory assistant. Her gentle, big-sisterly demeanor towards Tracy’s young ward Junior and bumbling Mike McGurk is amusing and likable, and her solicitude for Tracy’s worry over the disappearance of his brother comes off as completely sincere. In the later Tracy serials Steve and Gwen would largely become ciphers, but here they’re distinctive characters.

Junior (played by Lee Van Atta) and McGurk (played by the inimitable Smiley Burnette) round out our hero’s team. Van Atta’s Junior is prone to tag along when he’s not supposed to, but helps our heroes much more often than he hinders them, as opposed to Jerry Tucker’s more useless Junior in Dick Tracy Returns. Van Atta manages to balance his character between street-smart toughness and wide-eyed hero-worship of Tracy, and as a result is neither too obnoxious nor too cloying. Burnette’s bumbling McGurk is one of the most controversial sidekicks in any 1930s serials, but is not as destructive to the serial as some have claimed. His comedy bits don’t give him as much to work with as his scenes in Gene Autry’s movies did, but he handles them well–particularly his attempted radio broadcast and his attempt to spruce himself up when a female visitor is announced. The character is also allowed to be helpful in the fight scenes and doesn’t slow down the action–but, that said, his broadly comedic antics do seem out-of-place in a serial that’s moody and somber in most other regards; it was probably just as well for Burnette that Republic stopped trying to shoehorn him into their cliffhangers after this outing and let him concentrate on his B-western work instead.

Above: Smiley Burnette’s Mike feebly attempts to discipline Lee Van Atta’s Junior.

Dick Tracy features probably the creepiest group of bad guys in any Republic serial; there’s not a normal-looking heavy among the chapterplay’s triumvirate of villainy. The Lame One (who makes a memorably terrifying first appearance in Chapter One) is bad enough, with his limp, his raspy voice, and his ugly but-never-fully-seen face, while his lieutenants–the icy, emotionless Gordon and the grinning, demented Moloch–are the stuff of nightmares. As a child, this group of grotesques was simply too much for me–the idea of two such monsters as the Lame One and Moloch turning Gordon Tracy into yet another monster was too upsetting, and actually kept me from rewatching the serial until I reached maturer years.

Carleton Young is excellent as the “evil” Gordon (Richard Beach plays the character pre-transformation); his deep, modulated voice adds an air of inhuman deliberation to every evil deed he performs. John Picorri, as Moloch, gives perhaps the most memorable performance of his colorful but all-too-brief serial career. Whether petting his black cat, gloating with bizarre professional pride over the results of his fiendish operation on Gordon, or delightedly contemplating the prospect of performing the same operation on Dick, Picorri commands attention throughout. The Lame One is enacted (vocally, anyway) by the same performer who turns out to be him, so I won’t reveal his secret here; suffice it to say that the voice used fully compliments the villain’s sinister appearance.

Above: The Lame One, John Picorri, and Carleton Young.

The celebrated silent star Francis X. Bushman plays Tracy’s superior, Clive Anderson, and, by virtue of his earlier fame, is given high billing and a weekly card in the recap gallery, but not much in the way of screen time (not realizing Bushman’s silent-film fame when I first saw the serial, I was convinced that his high billing meant he would eventually turn out to be the Lame One). Byron Foulger, usually a nervous crook, has a memorable bit as a courageous Spider henchman who foolhardily tries to double-cross his boss in Chapter One and is subsequently stalked and murdered in a justly famous sequence. Edwin Stanley and Louis Morrell play the two Lame One suspects, a pair of congenial philanthropists (actually, their characters are never positively identified as such; Jack Mathis’ book Valley of the Cliffhangers explains how a scene introducing the two characters wound up on the cutting room floor). Lovable old-timer Milburn Morante has an excellent role as Death Valley Johnny, a gabby, cagey, and very good-natured prospector who “strikes it rich” and is subsequently menaced by the Spider Ring.

I. Stanford Jolley and Roy Barcroft both make their serial debuts as Spider Ring thugs (Jolley also pops up as a G-man, a hospital intern, and a reporter). Sam Flint plays a dignified jeweler, and Harrison Greene is a pompous foreign spy. John Dilson plays a Spider Ring member who’s eliminated by his boss early on in the serial, Ed LeSaint pops up as the Governor, Forbes Murray plays a kidnapped engraver, and Wedgwood Nowell has an extended guest appearance as an aircraft scientist, while Ann Ainslee plays his daughter. Alice Fleming, later the “Duchess” in Republic’s Red Ryder films, plays an orphanage matron, and Herbert Weber plays a murderous puppeteer. Buddy Roosevelt, Jim Corey, Al Ferguson, Al Taylor, and Monte Montague all play various Spider Ring henchmen, Walter Long pops up as a crooked bartender, and Bruce Mitchell plays Commander Brandon of the Coast Guard, who pops up to aid Tracy at several points in the serial. William Hopper, later to achieve television immortality as Perry Mason’s tireless aide Paul Drake, has non-speaking bits as two different dirigible pilots, one respectable and one villainous.

The serial’s two most controversial bit players deserve a paragraph to themselves: Ed Platt (otherwise known as Oscar) and Lou Fulton (otherwise known as Elmer). The Oscar/Elmer comedy team were one of producer Nat Levine’s strangest and most ill-advised ideas, as their atrocious “comedy” contributions to such early, Levine-produced Republic films as Gunsmoke Ranch testify. Their “humor” largely consists in Elmer’s infantile stammer and Oscar’s slow, agonizing drawl, but, that said, they only appear very briefly in Dick Tracy and aren’t anywhere near the blot on the serial that some have made them out to be. In fact, they are marginally amusing in the context of this cliffhanger, as their slow-witted responses to hitchhiking Ralph Byrd’s attempts to get them to follow a Spider car provide a rather funny contrast to the fast-moving and dead-serious nature of the rest of the serial.

The serial’s music score (by Alberto Colombo) is quite memorable, with some fine pulsating chase music and some fine ominous pieces to herald the appearance of the Lame One and his two horrible lieutenants. The music over the opening credits is quite good, and the credit sequences themselves–depicting as they do several of the serial’s key places of action–make fine openings to Tracy’s chapters. The cliffhanger’s cinematography is also first-rate, particularly during the already-mentioned Bay Bridge attack, Moloch’s attempted operation on Dick Tracy, and the Lame One’s first appearance in Chapter One. The cameramen in question, Edgar Lyons and William Nobles, would go on to give some good atmospheric touches to The Fighting Devil Dogs and other late-thirties Republic serials.

Dick Tracy might represent an early stage in Republic serial-making, but its great hero, memorable villains, fast-moving plot, and fine location work, earn it a place alongside its more acclaimed successors. Serial scholar Raymond William Stedman said it best in his The Movie Serial Companion: Book Two, when he referred to this chapterplay as an “unpolished diamond.”

Above: Ralph Byrd tersely and authoritatively breaks down the hidden clues in an extortion note, for the benefit of a squad of G-men.

I have always been quite fond of this serial in spite of its shortcomings. It is just a great effort “all the way to the sprocket holes”. Some reasons are subjective – like Nat Levine produced it, and it’s clearly in the Mascot mold but a lot more polished. There are many fine moments, especially the personal side of Tracy – how he reacts to the old woman complaining about the buzz from an abandoned plant, and my favorite the “I’ll find those yellow coyotes” promise to the unconscious prospector. I also think Smiley is quite tedious, but Oscar and Elmer really cracked me up. Levine did have a fondness for this type of humor but given his near clairvoyant ability to judge what audiences wanted I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt. Ordinarily not my venti of Chai.

A couple of fun moments – thought I saw Donald Kerr as a reporter in an early episode, unnamed but I’ll bet it was Happy Hapgood. Also glad to see Joe survived the Undersea Kingdom and got over his fear of submarines to take a job on one in this serial. Some exteriors of the Republic front office if I’m not mistaken. But personal affections aside, compared to efforts like Secret Agent X-9 or Red Barry the plot, acting, and action are far superior.

Just watching now…up to 9th chapter…Smiley a little out of place but not as bad as I read about in other reviews..have been watching serial westerns this is first non-western serial ..so far Ok ….

Much better than its critical reception might indicate, and one that features an extremely interesting cast of characters (heroic and villainous), great action and locations, and some genuinely terrific special effects. Even the occasional bits of “comedic” business are fairly tolerable and don’t interfere with the storyline in any appreciable way. All in all, a very worthy start to a great series.

One thing that I’ve never understood, and I hope someone might clarify – why use two different performers for the Gordon Tracy character? I understand that he has been “transformed” by Moloch and that his appearance has been somewhat altered as a result, but it seems that a satisfactory effect could have been achieved much more simply via the use of makeup rather than by completely changing actors. I wonder if they didn’t think Richard Beach was up to conveying the intensity displayed in Carleton Young’s performance.

I think they might also have wanted to use a different actor in order to explain why Tracy doesn’t recognize Gordon as the Lame One’s chief henchman, even though they meet to face-to-face several times after Gordon’s surgery. As I recall, Tracy doesn’t realize he’s been fighting his own brother until Moloch tells him directly in Chapter Fourteen.

That never occurred to me, but it makes perfect sense and makes it much more plausible as to why he didn’t recognize his own brother.